As we have moved into a primary cycle and the subject of the working class is on the lips of activists and politicians, I know the images that term evokes in the minds-eye of many who hear it—hard hats, lunch boxes and assembly lines—often male, and often white. Organized labor and unions get mentioned, but rarely when one thinks of unions, other than perhaps SEIU or organized teachers do we think of women.

Many of you know I went to an annual women’s gathering this weekend where I also celebrated my birthday. Hosted by one of my sisters from the Young Lords Party who is a union organizer, the gathering consists of mainly women of color, who are activists, and artist-activists from different age sets. Some of us have been attending for years. This year a sister I’ve wanted to meet for many years was there. We had never met, though we are both in the same film, “She’s Beautiful When She’s Angry,” which documents the second wave of feminism, and we know many of the same people.

I wanted you to meet her too. Her name is Linda Burnham, and she is the National Research Director for the National Domestic Workers Alliance.

She is a sister with a long history of activism.

Linda Burnham has worked for decades as an activist, writer, strategist, and organizational consultant focused on women’s rights and anti-racism. Most recently she has been serving as the National Research Coordinator of the National Domestic Workers Alliance (NDWA) and prior to that, she provided organizational consulting to Domestic Workers United and facilitated the Gender Justice from the Grassroots Inter-Alliance Dialogue gathering in March 2010.

Linda Burnham is a co-founder and former executive director of the Women of Color Resource Center. The Women of Color Resource Center is a community-based organization that links activists with scholars and provides information and analysis on the social, political and economic issues that most affect women of color. Burnham founded the center to provide a strong institutional base for an agenda that recognizes the crucial interconnections between anti-racist, anti-sexist and anti-homophobic organizing.

Burnham was a leader in the Third World Women’s Alliance, an organization that grew out of a women’s caucus in the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and that, early on, challenged the women’s movement to incorporate issues of race and class into the feminist agenda. She has participated in conferences and meetings with women in Kenya, Tanzania, Zambia, and Cuba, returning with insights about the global factors that affect women’s status and the unique ways in which women organize to create change in their communities.

Talking with Linda was exhilarating, and as with most black Americans, we have a shared history of domestic workers in our family trees. I was reminded that it has been a while since I’ve written about the work being done organizing for the rights of domestic and home care workers, a struggle she has played a major role in. She spoke of her respect for the leadership of Ai-jen Poo.

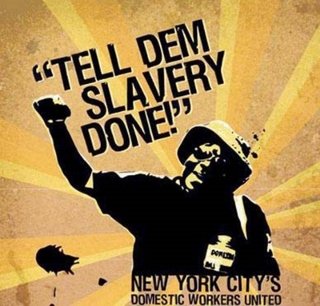

Ai-jen Poo is the Director of the National Domestic Workers Alliance and Co-director of the Caring Across Generations campaign. She is a 2014 MacArthur fellow and was named one of Time 100’s world’s most influential people in 2012. She began organizing immigrant women workers nearly two decades ago. In 2000 she co-founded Domestic Workers United, the New York organization that spearheaded the successful passage of the state’s historic Domestic Workers Bill of Rights in 2010.

Bernham is co-author, with Nik Theodore of “Home Economics: The Invisible and Unregulated World of Domestic Work” a report issued in which should be required reading for anyone with an interest in the intersections of race, gender and class in our economy.

How many domestic workers are there in the U.S.?

According to the report (published in 2012) :

The domestic work labor force is large and growing. The Census Bureau’s annual survey, the American Community Survey [ACS], finds that, from 2004 to 2010, the number of nannies, housecleaners, and caregivers working in private households and directly paid by their employers rose from 666,435 to 726,437, an increase of nearly 10 percent.

The actual number of domestic workers undoubtedly is far higher. These ACS figures do not take into account workers who are hired through placement agencies or those who work for private cleaning companies. Nor do they count some types of workers who could be considered domestic workers, such as cooks or chauffeurs. Furthermore, categorical overlap and fluidity complicates how domestic workers are counted. For example, a caregiver to an elderly person might perform many of the same functions as a home health aide, and vice versa.

We also may reasonably presume that domestic workers, a sector of the population with a large proportion of undocumented immigrants, are undercounted in the ACS due to reluctance on the part of many to share information with governmental entities, and because of language barriers. Researchers have confirmed that the Census Bureau undercounts undocumented immigrants for these reasons, as well as other inadequacies in data collection methods.

Ai-jen Poo states that in the United States there are somewhere between one and two million domestic workers, “depending on who you ask, and how you count.”

A summary of the report is available online:

Domestic workers are critical to the US economy. They help families meet many of the most basic physical, emotional, and social needs of the young and the old. They help to raise those who are learning to be fully contributing members of our society. They provide care and company for those whose working days are done, and who deserve ease and comfort in their older years. While their contributions may go unnoticed and uncalculated by measures of productivity, domestic workers free the time and attention of millions of other workers, allowing them to engage in the widest range of socially productive pursuits with undistracted focus and commitment. The lives of these workers would be infinitely more complex and burdened absent the labor of the domestic workers who enter their homes each day. Household labor, paid and unpaid, is indeed the work that makes all other work possible.

Despite their central role in the economy, domestic workers are often employed in substandard jobs. Working behind closed doors, beyond the reach of personnel policies, and often without employment contracts, they are subject to the whims of their employers. Some employers are terrific, generous, and understanding. Others, unfortunately, are demanding, exploitative, and abusive. Domestic workers often face issues in their work environment alone, without the benefit of co-workers who could lend a sympathetic ear.

The social isolation of domestic work is compounded by limited federal and state labor protections for this workforce. Many of the laws and policies that govern pay and conditions in the workplace simply do not apply to domestic workers. And even when domestic workers are protected by law, they have little power to assert their rights.

Domestic workers’ vulnerability to exploitation and abuse is deeply rooted in historical, social, and economic trends. Domestic work is largely women’s work. It carries the long legacy of the devaluation of women’s labor in the household. Domestic work in the US also carries the legacy of slavery with its divisions of labor along lines of both race and gender. The women who perform domestic work today are, in substantial measure, immigrant workers, many of whom are undocumented, and women of racial and ethnic minorities. These workers enter the labor force bearing multiple disadvantages.

There are also links to key findings, and recommendations.

On Mother’s Day of 2013, I wrote “Domestic workers and caregivers—fighting for their rights.” Since that time there have been some victories. Gov. Jerry Brown of CA, who vetoed the Domestic Workers Bill of Rights in 2012, after two vetoes finally signed the legislation in September of 2013, which went into effect in January of 2014.

In June of this year Oregon became the fifth state to pass a bill of rights for domestic workers.

Oregon’s domestic workers gain labor protections as Gov. Kate Brown signs new law

The governor signed Senate Bill 552 on Wednesday extending provisions for overtime pay, rest periods, paid personal time off and protections against sexual harassment and retaliation to an estimated 10,000 domestic workers in Oregon. The measure passed the Senate in late April and the House in early June, making Oregon the fifth state to offer basic protections to a class of workers who historically have been excluded from federal and state labor laws.

Since 2010, New York, California, Hawaii and Massachusetts, working with the National Domestic Workers Alliance, have passed laws guaranteeing similar rights.

Sen. Sara Gelser, D-Corvallis, chief sponsor of the Oregon bill, said it was the right thing to do, noting that 95 percent of domestic workers are women and many are immigrants and many are people of color. A similar bill passed the Oregon House two years ago but stalled in the Senate, she said. “Now domestic workers will be able to adequately provide for their own families, and finally be protected for the valuable work that they do,” Gelser said. “And employers who hire domestic workers will have a standard to look towards which will help to ensure quality care for their families.”

The new law takes effect January 1, 2016, and directs the Oregon Bureau of Labor and Industries to adopt rules to implement it.

Five states. That’s only 10% at this point. We have to do better. I honor the women who have fought so long and hard for these gains, but as you can see we have a long way to go.

This isn’t just a U.S. issue. In “Bad housekeeping: the plight of domestic workers,” Kevin Redmayne just wrote:

In Colombo, the sweltering capital of Sri Lanka, the Domestic Workers Union is picketing outside the Supreme Court. Sarath Abrew, a high-ranking judge, has been accused of sexually assaulting a chambermaid, fracturing her skull and leaving her for dead. The protesters are not only demanding justice, but also new laws to safeguard their rights. In an exploitative industry, this can’t be just another day – the violence has to stop.

Right now, there are 53 million people working as domestics in countries all over the globe, amounting to 1.7% of the world’s employed. Of this group, 83% are female, which means 1 in 13 wage-earning women is in domestic work. More worryingly, so are 17.2 million children, many too young to give informed consent. The International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates that domestic workers earn less than 50% of the average salary of any particular nation. This means that workers in the developing world could earn a salary lower than $8,000 a year or, worse still, no salary at all. Job titles include housemaid, servant, cook, gardener, governess, babysitter or care-giver. We rarely use the term ‘slave’ but in many cases this is effectively what the workers are.

The ILO recently warned of the ‘invisibility’ of domestic work. The reality is much more damaging than poor pay and long hours. Many employees have no legal protection and are often given unlawful contracts, unfair terms and unethical job descriptions. They are perilously close to being victims of crime or destitution.

Domestic work is essential work, but because so many of these jobs are done by women, both their labor and lives are devalued.

Support the Domestic Workers Alliance to help carry the struggle forward.

Right now the NDWA is working on CT

http://www.domesticworkers.org/connecticut-bill-of-rights

and IL

http://www.domesticworkers.org/illinois-bill-of-rights

Thank you for bringing attention to these women and their union. The traditional unions, in many ways contributed to their own decline because their members were white males, their leadership was white male and they had no interest in representing the many millions who could benefit from unionization in low wage, low benefit jobs.

SEIU changed that and their focus on improving the lives of all workers has led to a better understanding of the value of unions. Union membership is starting to reflect the diversity in our society and will continue to grow as people realize the strength that comes from banding together to improve wages, benefits and working conditions.

I’ve been working with folks from SEIU/1199 since the sixties – they are awesome organizers – and are a rainbow of backgrounds.

I was just thinking of that a few weeks ago when I was in a rehab place. ALL the work was done by women who were aides and did not get the respect that nurses and doctors got.They worked very hard, often with abusive patients. I was and am in awe of the. I would not be where I am today without their care and kindness.

As for SEIU, come election time, they sometimes sponsor phone banking and I have gone there to work for Obama and Sherrod Brown. Wow, are they ever organized. Totally impressi9ve.

Thanks for sharing that Sis – so many people act like they are invisible – and I’ve seen them abused by patients and some doctors

In the 1950s through 70s – that I know of, probably 1940s as well – in TX domestic workers were treated by the state anyway as any other non-agricultural laborer. Jobs were listed through the state employment office along with general construction and other “non-skilled” – for full-time, part-time, or day labor situations. Employers had to pay at least minimum wage, regular hours (including overtime for an over 40-hour work week) and provide safe working conditions. By the 1980s domestic workers were no longer a part of the state employment office listings. Sigh.

Wow – so the state went backwards instead of forward?

I found this article about organizing in TX

http://www.publicnewsservice.org/2013-07-11/livable-wages-working-families/domestic-workers-in-texas-are-fighting-for-their-rights/a33430-1

Lots of stuff went backwards in TX since the 1970s – and is doing it’s best to go further back and faster. And it’s a bunch economic, as usual. In the 50s & 60s TX was booming – between the fossil-fuel boom, interstate highways being built, the space program being ramped up, and multiple other largely federally-funded projects (San Antonio alone had 3 USAF bases – and the best burn-hospital in the nation) money was coming in right, left, and sideways and most of it was going to the middle classes. We got “stagflation” in the 1970s – and “blame the gummint” never has worked well when most of your revenue comes from the gummint – which hit the middle class allowing the oligarchy to start their old tried-and-true divide and conquer strategies again. And the targets, as usual, were/are “Mexicans”, blacks, and women. TX has been going downhill ever since and definitely picking up speed since Rove’s nasty campaign tactics put W in the governor’s mansion. TX is almost in freefall right now.

I have never understood people whose racism and xenophobia is so strong that they vote against their own self interests.

I guess I never will.