From the Motley Moose Archives … (Photobucket images are no longer available and have been downsized)

I have touched on the topic of stigma against the mentally ill before, so I’m taking bits and pieces of research from that previous diary. But I’d like to revisit it here in a slightly different way. There was a statement made in another diary the other day that brought this to mind. Someone elsewhere in the blogosphere suggested that the mentally ill should be imprisoned “just like sex offenders” until doctors could determine that they were safe for society. I’m assuming that it was not intended as it was written (I certainly hope not), but unfortunately, there are many out there who do actually think this way.

Ouch.

Ouch.

So what is stigma, exactly?

stigma

n. pl. stig·ma·ta (stg-mät,

mt, stgm) or stig·mas1. A mark or token of infamy, disgrace, or reproach

2. A small mark; a scar or birthmark.

3. Medicine A mark or characteristic indicative of a history of a disease or abnormality.

4. Psychology A mark or spot on the skin that bleeds as a symptom of hysteria.

[. . .]

8. Archaic A mark burned into the skin of a criminal or slave; a brand.

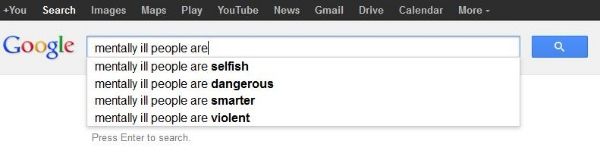

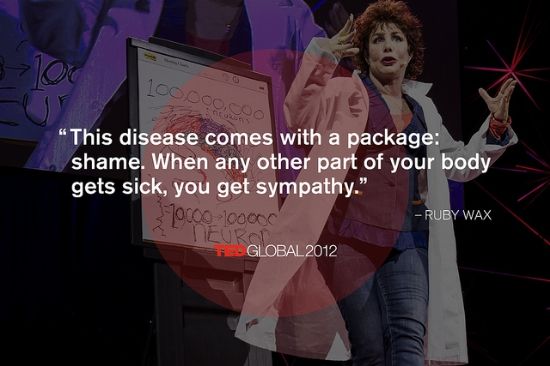

Despite our growing knowledge of a variety of mental illnesses and their myriad etiologies and symptoms, we have not made proportional strides in dispelling public stigma against the people who suffer from them.

To the contrary, over the years we have seen regression rather than progression in the fight against stigmatization.

It is the 21st century, and though evidence-based research has shown us that mental illness is a real medical disorder, stigma is on the rise instead of on the decline. David Satcher, [fmr.] US Attorney General writes, “Stigma was expected to abate with increased knowledge of mental illness, but just the opposite occurred: stigma in some ways intensified over the past 40 years even though understanding improved. Knowledge of mental illness appears by itself insufficient to dispel stigma.”

Stigma is a complicated concept within our society. While relatively simple definitionally, the causes, mechanisms, and consequences of social stigma are multitudinous and complex. Much of it seems to be based in fear born out of ignorance. You can find stigma, of one sort or another, most anywhere you look. Stigma will thrive in society wherever ignorance or fear or hatred of that which is “different” are acceptable mentalities. The tendency to stigmatize, label, and set certain groups/individuals apart from the rest of society as “other” is, to an extent, human nature. The need to categorize people, places, and things is normal — it’s just a function of how our brains work. We run into problems, however, when we begin allowing categories and labels to exclude and define people.

Stigma is a complicated concept within our society. While relatively simple definitionally, the causes, mechanisms, and consequences of social stigma are multitudinous and complex. Much of it seems to be based in fear born out of ignorance. You can find stigma, of one sort or another, most anywhere you look. Stigma will thrive in society wherever ignorance or fear or hatred of that which is “different” are acceptable mentalities. The tendency to stigmatize, label, and set certain groups/individuals apart from the rest of society as “other” is, to an extent, human nature. The need to categorize people, places, and things is normal — it’s just a function of how our brains work. We run into problems, however, when we begin allowing categories and labels to exclude and define people.

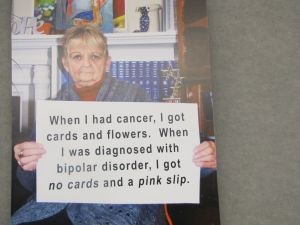

Stereotyping, stigmatizing, and treating these people differently creates a vicious cycle for many sufferers. It makes life significantly harder for individuals who are already struggling. Prejudice and stigma negatively impact the lives of countless mentally ill individuals and their families. Stemming from fear, ignorance, and incomprehension, social stigma — whether relatively mild or outright hateful — is inevitably harmful to those exposed to it. It can lead to severely decreased self-esteem, feelings of isolation and rejection, feelings of self-loathing, diminished or damaged support networks, high unemployment rates, overt or covert hostility, increased levels of stress, fear of seeking help (even for doctors who are mentally ill), and many other problems, ranging from minor inconveniences to severe hardships. The spectrum of complex, difficult emotions experienced by many mentally ill people due to stigma is broad.

For those with mental illness the stigma experienced can result in a lack of funding for services, difficulty gaining employment, a mortgage or holiday insurance. Ultimately, feelings of stigma cause people to delay seeking help or even deny they have symptoms in the first place.

The Guardian, Crazy Talk: The language of mental illness stigma

We know that stigma is not just a word but a toxic concoction of ignorance and fear, of prejudice and power play, that continues to have a real and substantial impact on the daily experiences of thousands of people, in relationships with friends and family, in attempts at finding and keeping employment, and even in accessing healthcare.

The Guardian, The most toxic issue facing those with mental health problems is stigma

Persistent stigmatization of mentally ill persons can ultimately cause them to stigmatize themselves.

Self-stigma also can lead to isolation, lower self-esteem and a distorted self-image. “People with a mental illness with elevated self-stigma report low self-esteem and low self-image, and as a result they refrain from taking an active role in various areas of life, such as employment, housing and social life,” according to David Roe, professor and chair of the department of community mental health at the University of Haifa.

World of Psychology, When Mental Illness Stigma Turns Inward

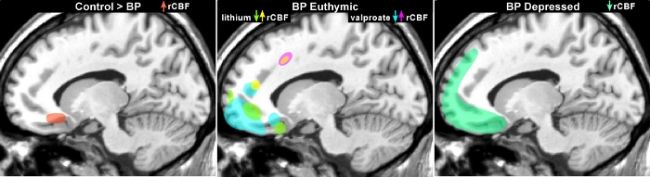

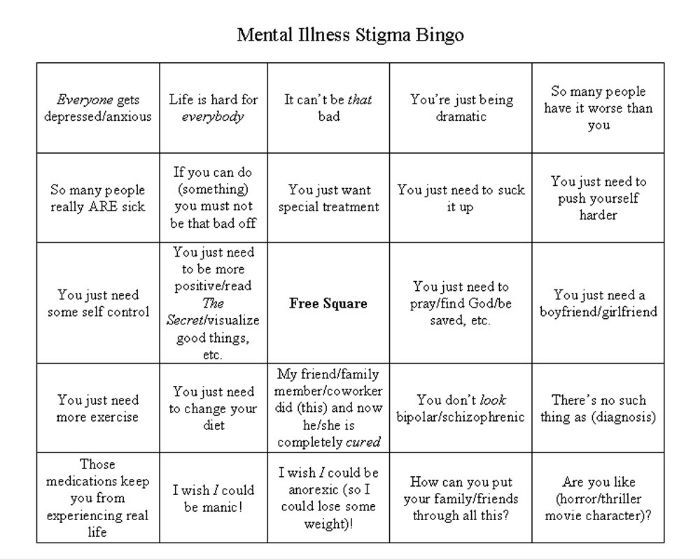

Of those who know me well, a small number eventually find out that I am bipolar. It’s not something I advertise to the public, and it has, at times, been an enormously debilitating force in my life. Even though I am educated about my problems and know better, many times I have berated myself harshly for my “weakness” or even found fault in my very existence. Early on, I doubted my right to live based upon the difficulties inherent to the disorder, and I have since sometimes felt deeply ashamed of it. Not everyone who has learned of it has been understanding. Not at all. I have been told I was “undisciplined,” that the illness was “fake” or “manufactured,” that I was “making excuses,” that I was “scary,” that I needed to “go back to church,” that I was “just manipulative,” that I “needed a knot jerked in my tail,” that I had “taken advantage of loving parents,” that I was “just too emotional,” that that that that that……

Of those who know me well, a small number eventually find out that I am bipolar. It’s not something I advertise to the public, and it has, at times, been an enormously debilitating force in my life. Even though I am educated about my problems and know better, many times I have berated myself harshly for my “weakness” or even found fault in my very existence. Early on, I doubted my right to live based upon the difficulties inherent to the disorder, and I have since sometimes felt deeply ashamed of it. Not everyone who has learned of it has been understanding. Not at all. I have been told I was “undisciplined,” that the illness was “fake” or “manufactured,” that I was “making excuses,” that I was “scary,” that I needed to “go back to church,” that I was “just manipulative,” that I “needed a knot jerked in my tail,” that I had “taken advantage of loving parents,” that I was “just too emotional,” that that that that that……

It’s NOT just my imagination that keeps me from telling people.

When I do tell someone, I invariably feel naked, vulnerable, and exposed. The occasions upon which I have been “outed” about my illness have brought on intense feelings of horror and helplessness. It’s a “closet” I do not step out of lightly without considerable thought. Allowing my illness to become public knowledge could very likely bring about serious negative consequences, especially professionally.

Still, I should know better and advocate on my own behalf and the behalf of others as much as possible.

But I often don’t.

For the most part, throughout my life, I have determinedly hidden my mental illness. When I am around people I do not know well, I stuff it away in my most secure closet and lock the door tight. Considering the pervasive social stigma with which mentally ill people are faced, hiding usually it feels like the safest, most palatable option for me.

I have always been a bit of a coward about it all, for a plethora of reasons. I found my first reason when I was about five, and it became one of the defining factors of my life for many years. My “nutty” paternal aunt was diagnosed bipolar, and everyone in the family knew it. My protective mother immediately began watching for similar symptoms in me. She has admitted in recent years that she watched me so closely — fearful that something was wrong — that she she sometimes feels she “made me crazy.” Of course, that is not the case, but I was well aware of being watched. My mother was always making little comments about how I looked “down” or “depressed,” or asking what was wrong with me. I felt like a bug in a jar — constantly being studied and examined. It wasn’t a good feeling for a kid. I became hellbent on hiding my problems. I was going to be normal, by god, no matter how “insane” I drove myself trying to accomplish that normality.

I have always been a bit of a coward about it all, for a plethora of reasons. I found my first reason when I was about five, and it became one of the defining factors of my life for many years. My “nutty” paternal aunt was diagnosed bipolar, and everyone in the family knew it. My protective mother immediately began watching for similar symptoms in me. She has admitted in recent years that she watched me so closely — fearful that something was wrong — that she she sometimes feels she “made me crazy.” Of course, that is not the case, but I was well aware of being watched. My mother was always making little comments about how I looked “down” or “depressed,” or asking what was wrong with me. I felt like a bug in a jar — constantly being studied and examined. It wasn’t a good feeling for a kid. I became hellbent on hiding my problems. I was going to be normal, by god, no matter how “insane” I drove myself trying to accomplish that normality.

What this determination actually accomplished, however, was a delay in seeking treatment that I desperately needed during my late teens. So afraid of public disapproval and stigma — and so fearful of disappointing my family — I hid my symptoms as long as I was able. I cloaked them in socially acceptable activities when I could, and engaged in less acceptable behaviors when I felt that I had to. Consequentially, the bipolar disorder had fully manifested itself in the form of a full-blown manic episode by the time I got any help. Even then, for as badly as I clearly needed treatment, I did not seek it on my own — and in fact fought it tooth and nail. Fortunately, the people around me could see my need, too, because I could no longer hide my problems.

To a degree, the stigma — the fear of shame and shunning — was almost as much to blame for my long-term suffering and eventual institutionalization as the illness itself. I did not get help until it was too late to be preventative. I did not seek help at all, despite my dire need. After over a decade of hiding my problems out of my own shame and ignorance, I had become truly incapable of seeking out aid on my own. I was willing to live in mental and emotional agony rather than go to outsiders for help with my “abnormality.”

Such is the power of stigma for some of us… a dark closet of our mind’s own making.

Shortly after my diagnosis, I returned to (a different) school, and I began studying psychology. I was interested in the workings of the mind — mine and others’ — and I wanted to understand the brain better. Over time, this tentative curiosity about the mind transformed into profound empathy and compassion for others who had experienced suffering similar to my own. I chose to pursue a career in the mental health field in order to help the people who needed it — many of whom society routinely shunned and stereotyped.

I am not much of an advocate. I always hide what I am at work and in school, and I feel uncomfortable in situations where I fear my “secret” might be uncovered. I have tried to educate others while working in the counseling field, but I have done so purely from an academic standpoint. As a rule, I am not much of one to share my story “in real life,” even with the people who might most need to hear it. It has always unsettled me a little that I am, from a clinical diagnostic perspective, technically “sicker” than most of the clients and patients I have counseled. I fear that such knowledge would not inspire comfort or confidence in the people I work with. Those of us who have played the roles of both patient and healer have, perhaps, a unique perspective. I hope that in time I will find more effective ways to utilize that perspective and share what I have learned with others, particularly those who are still suffering.

In combating stigma, we walk a fine line. It is difficult to educate an uninformed person about mental illness in a way that will not create negative thoughts/associations, while still acknowledging and imparting the seriousness of mental illness and the detrimental effects it can have on sufferers’ lives. To paint a picture of mental illness as “not a big deal” or even as something which does not, to some degree, set the mentally ill apart from others… is to minimize and possibly even trivialize it. Varying disorders differ in their “severity” and their potential to impact the mentally ill individual and those around him/her, and even people with the “same” disorder will experience symptoms in different ways along a continuum. I do not discount the pain experienced by anyone due to mental illness, regardless of the diagnosis, but I will say that some disorders do have greater potential to cause definite harm to the sick individual (and others). Even now, I’m conscious of not expressing myself as well as I would like about this issue. So how do we adequately explain such nuanced concepts to people who don’t know and may not even wish to listen?

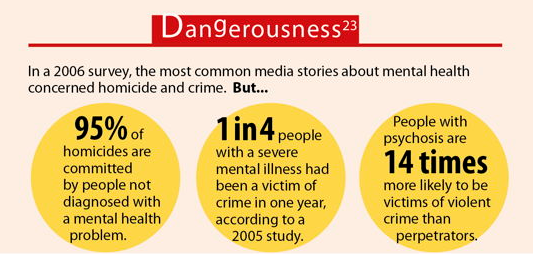

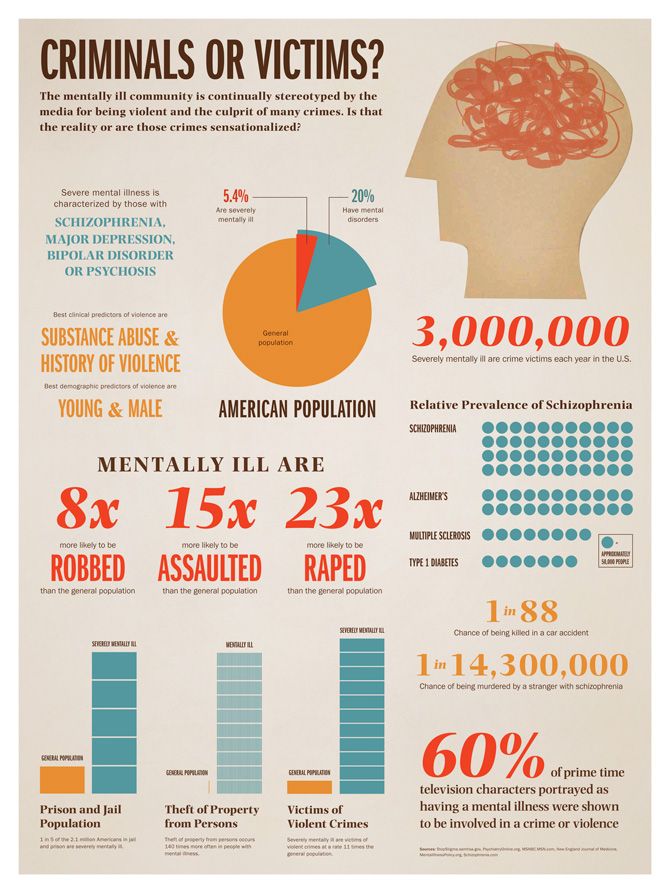

There are plenty of factors which affect the development, maintenance, and strength of stigma. And indeed, though the mentally ill are often stigmatized and discriminated against as a group, certain mental illnesses arouse more fear and antipathy in the minds of “healthy” individuals than others. Most people rightfully view individuals suffering with anxiety disorders as being quite distinct (in terms of symptoms, treatment, and prognosis) from those living with schizophrenia. There’s nothing wrong with recognizing very real differences, and dissimilar mental health problems shouldn’t be “lumped together” inappropriately. The problem arises when people assign unrealistically negative traits/characteristics to a group and separate them from “normal” people so completely that the stigmatized individuals are effectively stripped of their humanity in the eyes of the ignorant.

So how do we approach these problems?

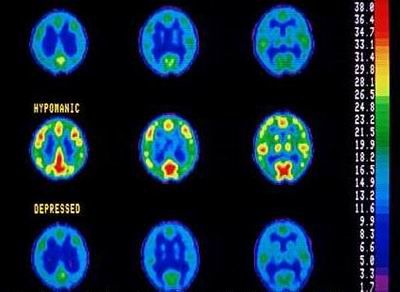

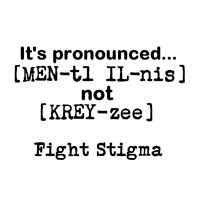

People have plenty of ideas about that too. Some tactics include educating others, becoming an advocate and spreading the word, getting involved in changing public policy, eliminating derogatory words (e.g., “crazy,” “psycho”) from one’s vocabulary, supporting anti-discrimination programs like Time to Change, encouraging and supporting the mentally ill in treatment, reframing mental illness by calling it a “brain disease,” and supporting efforts to obtain more and better services and treatment for the mentally ill.

Change strategies for public stigma have been grouped into three approaches: protest, education, and contact (12). Groups protest inaccurate and hostile representations of mental illness as a way to challenge the stigmas they represent. These efforts send two messages. To the media: STOP reporting inaccurate representations of mental illness. To the public: STOP believing negative views about mental illness.

[. . .]

Education provides information so that the public can make more informed decisions about mental illness. This approach to changing stigma has been most thoroughly examined by investigators. Research, for example, has suggested that persons who evince a better understanding of mental illness are less likely to endorse stigma and discrimination.

[. . .]

Stigma is further diminished when members of the general public meet persons with mental illness who are able to hold down jobs or live as good neighbors in the community. Research has shown an inverse relationship between having contact with a person with mental illness and endorsing psychiatric stigma.

World Psychiatry, Understanding the impact of stigma on people with mental illness, image added

I’m sure you can all think of other things people could do to help combat stigma. Discussing all the many different methods [PDF] people have conceptualized to fight stigmatization of the mentally ill is well beyond the scope of a single diary.

Providing education is important, but as for me personally? I find myself pausing at times. How do I honestly, accurately educate people about someone such as myself without arousing unease, disgust, or fear in the people I am attempting to teach? I was once very sick, and many aspects of my journey are unpleasant to hear or talk about. How could someone tell my story, with or without explicit details, with any degree of truth and still expect empathy and understanding from the “unenlightened”? Perhaps as time passes I will become more comfortable advocating by using my own experience.

Providing education is important, but as for me personally? I find myself pausing at times. How do I honestly, accurately educate people about someone such as myself without arousing unease, disgust, or fear in the people I am attempting to teach? I was once very sick, and many aspects of my journey are unpleasant to hear or talk about. How could someone tell my story, with or without explicit details, with any degree of truth and still expect empathy and understanding from the “unenlightened”? Perhaps as time passes I will become more comfortable advocating by using my own experience.

When it comes to my current day functioning, I still have plenty of problems. Many of them are unrelated to bipolar disorder, however, and are instead longstanding character defects I just need to work diligently on. With regard to the bipolar disorder itself, I am certainly not asymptomatic, but life is better (thanks in large part to a brilliant psychiatrist who has repeatedly saved my life). I think I am a decent person, and when I do the things I know to do (take meds, hydrate, eat right, exercise, light therapy, counseling), I am pretty damn stable overall.

At first I hesitated to use the word sufferer to describe people living with mental illness, but in the end, I couldn’t get around the fact that it is an accurate description of what we deal with day by day. Some days are better than others. Maybe it’s not an empowering word, but I believe it to be true. Bipolar disorder does not define me, but it is inextricably interwoven into the fabric of my life and my being. And I have suffered — and still suffer — for its presence in my mind. Refusing to acknowledge this reality doesn’t make it any less real… so why sugarcoat? This is not to say that I’m miserable, because I don’t typically consider myself a miserable person. But there are some hard truths about living with my illness that are sometimes difficult to cope with. I am very fortunate to have an overwhelmingly strong support network. Not everyone is so lucky. There are things people can do to help, however, and hopefully legislation will gradually move us toward decreased stigmatization of the mentally ill and increased access to affordable services.

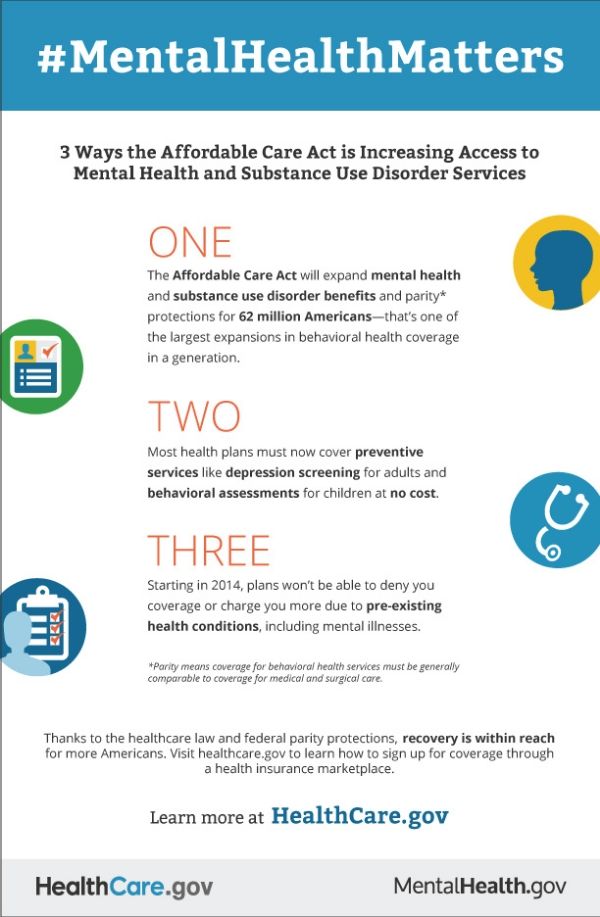

Approximately 90% of people with serious mental illnesses are unemployed. This means they do not have an employer-based health insurance plan. If they try to purchase their own insurance, they find many barriers. Currently, insurers can refuse to sell or renew policies based on a person’s health or mental health, deny coverage for any pre-existing condition (thereby failing to pay for ongoing mental health treatment), or issue a policy with limits on the length of covered treatment. Even when such policies can be found, they are often extremely expensive and do not provide good coverage.

The Affordable Care Act addresses these fundamental problems and will significantly improve access to health and mental health care for people with psychiatric disabilities. Under this law:

- Health insurers will have to sell and renew policies to all who apply (called “guaranteed issue and renewal”).

- Insurers cannot deny coverage for a pre-existing condition.

- No health plan can have a lifetime or annual limit on certain benefits.

- Insurers cannot charge people with poor health more than others – premiums (the amount a person pays to have insurance) may only vary by a limited amount and only on the basis of a few factors (tobacco use, age, geographic area and family size).

- Health insurers cannot discriminate based on a person’s mental or physical disability.

- Young adults (up to age 26) must be allowed to remain on their parents’ health insurance, if their parents so desire.

These provisions will greatly improve access to quality health care and to mental health care for people with psychiatric disabilities who either have no insurance today or have insurance that is very limited or very expensive. The law does not require that individuals lose their existing health care coverage.

Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law, How Will Health Reform Help People With Mental Illness? [PDF]

Of course, the mental health cuts that have taken place in many states are a step in the wrong direction. Poor funding for mental health is an onging crisis [PDF], and this is one of the reasons advocacy is so important. My hope is that one day quality, affordable mental health services will truly be available to all who need them. Fighting stigma is an important element of this quest, as increased public support would help influence public policy.

We have a long slog ahead of us.

One last thought on the way the public perceives mental illness… Even when people think they are being nice, the stereotypes they buy into frequently still shine through. I recently had someone tell me he just couldn’t imagine me having an “episode,” and that I “seem so normal.”

“You don’t act bipolar at all.”

Thanks. That’s not sarcasm. Really, thanks — because it was earnest, and the intent was kind. But the thought processes behind it were still a bit misguided. All I could really think to do was say with a smile…

“The result of lots of effort, support, counseling, and meds. But my treatment team and I thank you.”

(For those of you interested in discussing things at Big Orange, this is cross-posted there.)

This diary was originally posted in the Motley Moose in September 2013 and is reposted as mental illness – and forced institutionalization – is in the news again.

Very good – well, I’ll call it a reminder since I knew most (not all of course) of this. Most of my mother’s family is bi-polar to one degree or another although not officially diagnosed. Most did not seek medical help, for one reason or another – stigma and money being the biggest two – most self-medicated with alcohol in the older generations and marijuana in the younger. No, it did not miss me. But I’m one of the lighter ones – in earlier parts of my life I did seek counseling when I could find/afford it. I still wasn’t officially diagnosed so I can’t truthfully say for sure it’s bi-polar in me or my family but it certainly outpictures along a spectrum of what the one actually diagnosed and treated member of the family experienced. Taking care of my body has kept me balanced between the extremes enough to go on with. I’m lucky. We’ve got a long way to go on this in our society.

Here are some of the news reports:

Trump: ‘We’re Going To Have To Start Talking About Mental Institutions’

Administration pressed to expand mental health treatment

Mental institutions are even more expensive than jails. That’s why the Reagan administration shut them down. Nobody seems to have noted that most of the violence the mentally ill exhibit is towards themselves. And that they are victims of violence much more than they are the perpetrators of it. sigh.