![By U.S. Dept. of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) from USA [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](http://motleymoose.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/50th_Anniversary_of_the_Fair_Housing_Act_Opening_Ceremony_27561779548.jpg)

Myrdal suggested that racism was “irrational and pathological” and to

…open up the housing market would require an appeal to white Americans’ morality. Habit, culture, and emotions — all interacted to perpetuate housing segregation. To break open what Gunnar Myrdal called the “vicious circle” of segregation required systematic “scientific research” in service of “social engineering.” Source: Sweet Land of Liberty: The Forgotten Struggle for Civil Rights in the North by Thomas Sugrue, p. 213

Social scientists accepted the challenge, but rather than focusing on the inclusion of Black Americans into the political system, a significant number of social scientists wrote about prejudice and racism in terms of pathology and illness. Influenced by the rise of both fascism and Communism, academics had reflected on the “authoritarian” personality which responded to insecurity (defined in psychological terms) with hostility and aggression, and many proceeded to create an analogous link to race prejudice in the United States. According to this line of thinking, racial inequality was the result of white insecurity; in today’s terms, the racist suffered from a low sense of self-worth or poor self-esteem. Variously described as a neurosis, emotional weakness, and inadequacy, white insecurity was the core of all discrimination and prejudice.

African-Americans, on the other hand, damaged by racial prejudice, were considered to have a culture deformed by internalized white prejudice. This black “pathology” resulted in emasculated Black males who acted out with rage and “hyper-masculine” behavior and a Black matriarchy (viewed as a dangerous negative) which resulted in overbearing women. This dysfunctional dynamic made the creation of organized communities difficult, and the resulting lack of social controls led to a instability, the inability to achieve moral order, and a lack of sense of community. Crime and “ghetto behavior” was the direct result of internalized racism; segregation created “slum behavior.”

In short, racism was an illness that could be cured. The White American could overcome their insecurity and lack of self-worth, expressed through aggression, hate and violence, by living in communities with the very individuals who were the object of their prejudice. The Black American could be cured of their pathology by living in stable, moral communities which would enable them to overcome their own internalized racism. It is against this backdrop of racism as an illness-of-the-individual which could be cured through ongoing interaction between black and white Americans that Morris Milgram launched his career as an open housing activist and builder.

Why did Milgram resort to quotas, later labeled as “benign discrimination”, rather than building houses just building houses open for purchase to African-Americans?

Milgram was an open housing activist first and a builder second. Conversely, his Concord Park and Greenbelt Knoll partner, George Otto, was a builder and a Quaker who felt a commitment to racial justice, but was less-inclined to engage in a social experiment. Interestingly, it was Otto who pushed for an absence of quotas altogether and wanted to build houses for an underserved community (in the period between 1946 and 1953, only 45 homes in the Philadelphia area were available for purchase by African-Americans). But Milgram, fearful of creating a ghetto, with all of the connotations derived from the social science studies of the period, insisted that some method for achieving integration be used. There was ongoing debate between Milgram, Otto, and the Board of Directors before the 55/45% quota was eventually put in place.

Concord Park was a majority-black community by 1968 and almost 100% black by the 1990s. Did white flight occur there too? Was Concord Park, in fact, a failure?

Although one could technically argue that because Milgram’s dream of an integrated community was not maintained, Concord Park was a failure, the residents of the time would disagree.

For example, in 1957, the Institute for Urban Studies of the University of Pennsylvania conducted interviews with more than 90 percent of Concord Park’s white residents. Of the residents interviewed, 75 percent expressed “unqualified approval” of their neighbors, while another 11 percent expressed “general approval” with “some qualifications.” Survey participants mentioned only one person by name as being disliked, and this person was white. In fact, two of the white families interviewed stated that their black neighbors were generally superior to Concord Park’s whites. Other respondents remarked more generally about the overall neighborly feel of the development. “People who don’t even know you, wave because you live here, too,” stated one resident. “I wonder if that is true in an all-white development?” Another resident’s comments shed light on the widely held perception that blacks could not maintain property: “There was one family here that didn’t hang curtains for the longest time; it passed through my head that that must be a colored family, but you know what it was white. People think Negroes don’t keep their places up as well, but they’re wrong.” Source: The “Problem” of the Black Middle Class: Morris Milgram’s Concord Park and Residential Integration in Philadelphia’s Postwar Suburbs by W. Benjamin Piggott, PENNSYLVANIA MAGAZINE OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY Vol. CXXXII, No. 2 (April 2008)

In addition, although Milgram worked to maintain the quotas for as long as he legally could, he could not overcome the institutional advantages that whites had vs African-Americans. Nor could he fight the ongoing racism in the real estate industry as a whole; redlining was not made illegal until the passage of the Fair Housing Act in 1968. If a white Concord Park resident chose to move, whether for a location closer to their job or because they were seeking a larger home, there was little to stop them. However, an African-American didn’t have the same choices available to them, so moving away from Concord Park was a difficult proposition. And if a middle-class African-American family was seeking to become homeowners for the first time, Concord Park was one of the few areas open to them. Whites in Concord Park moved away for any number of reasons, but fear of their neighbors was not one of them; African-Americans remained because racism left them few other options.

Concord Park may not have been a failure, but the proposed, but unbuilt, development in Deerfield, IL sure was. What was the difference?

The easiest factor to identify that made Concord Park successful when Deerfield failed was that the Philadelphia area was Milgram’s home base, and as a result, he had ties throughout the community. He was a member of the local NAACP branch, was involved with the Fellowship of Reconciliation (which included a large number of Quakers), as well as being located in “Quaker country” with the American Friends Service Committee headquartered in Philadelphia. When he ran into stumbling blocks in getting Concord Park started, he had a network of activists to call upon for assistance. These activists were not new to the work of civil rights:

Yet, it should be noted that while Milgram’s task would prove difficult to achieve, significant sentiment in favor of integration did exist in the Philadelphia area. As historian Matthew Countryman notes, the region had seen an upsurge in civil rights activity in the years prior to Milgram’s decision to build Concord Park, a process that would create potentially important resources from which his project could draw. The strength of the Philadelphia NAACP, the existence of area-specific organizations like the Jewish Community Relations Council (JCRC), and the region’s Quaker legacy and its institutional manifestation, the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), resulted in significant civil rights progress in the immediate postwar years. Together these groups constituted the Fellowship Commission, which worked successfully for the establishment of a new city charter in 1951 that contained a Human Relations Commission designed to enforce antidiscrimination laws. Source: The “Problem” of the Black Middle Class: Morris Milgram’s Concord Park and Residential Integration in Philadelphia’s Postwar Suburbs by W. Benjamin Piggott, PENNSYLVANIA MAGAZINE OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY Vol. CXXXII, No. 2 (April 2008)

In Deerfield, Milgram had none of these resources and advantages. Although a Chicago architectural firm was designing the homes and there were local representatives for the company, Milgram was effectively an outsider…and a Jewish one at that.

Milgram, whose reputation as the “Johnny Appleseed of integrated housing” had followed him to the Midwest, became the target of the villagers’ animus. His outsider status and association with the socialist Workers Defense League — and his Jewishness — did little to endear him to Republican Deerfield. “The familiar cry of ‘Red!’ would be heard when Milgram’s name was mentioned,” wrote Harry and David Rosen in their sympathetic 1962 account of the controversy, But Not Next Door. “More than one loyal ‘integrationist’ expressed the private view that their row would be much easier to hoe if Milgram had been less politically controversial.” (Milgram, incidentally, had drifted from socialism toward mainstream Democratic politics after his stint at the WDL, weary, like many others, of the vicious infighting on the left during the 1930s and ’40s.) Source: “Housing Is Everybody’s Problem”: The Forgotten Crusade of Morris Milgram

Another factor which is less obvious is the difference in the siting of Concord Park (and Greenbelt Knoll) as compared to the Deerfield subdivision. Prior to World War II, black “suburbanization,” to the extent that it existed, generally consisted of working class African-American homeowners settling on unincorporated (and often unregulated) land on the outskirts of cities. They frequently built homes on land that was available (but not always owned) and maintained gardens or mini-farms with small farm animals to sustain self-sufficiency. These areas were tolerated by many cities, because they were self-segregated by their distance from the city center and did not encroach on the higher-quality housing stock available only to Whites. After World War II, with a housing crisis in full bloom, Levitt and Sons began to redefine the understanding of the suburb as a desirable and affordable place for the (white) middle class. Milgram embraced that idea on an integrated basis, but Concord Park maintained the spatial separation that had been part of Black “suburbs” up to that point. Although close to existing transportation hubs, it was adjacent to a then under-construction Pennsylvania Turnpike interchange, a cemetery, and close to a nearby pre-WWII Black “suburb”, Linconia. These effectively acted as barriers to further growth, and more importantly to fearful Whites, closed off “that colored development” from other all-white neighborhoods and subdivisions. In both Concord Park and Greenbelt Knoll, Milgram even built swimming pools, so all residents had a place to swim without having to deal with racial barriers at nearby community pools.

In Deerfield, however, Milgram abandoned this intentional use of geographical barriers. No one knows for sure why he walked away from this previously-successful approach; some surmise that Milgram felt that progress had been made in the area of open housing, and that such artificial barriers were no longer necessary. For whatever reason, the land Milgram purchased for the Deerfield project was close to the Deerfield village center and was just a short distance from one of the main roads in the village (for those who are curious, the current Jaycee Memorial Park and Mitchell Pool are built on the land Milgram had intended to develop). There was no way that Deerfield residents would have been able to ignore Black residents if the development had gone through. There was no way to create artificial barriers to constrain the growth of Black occupancy. In Deerfield, Milgram broke the white “rules” about spatially-isolated black residency, and white residents fought back.

So, with this series ending, what are the lessons learned and paths for the future?

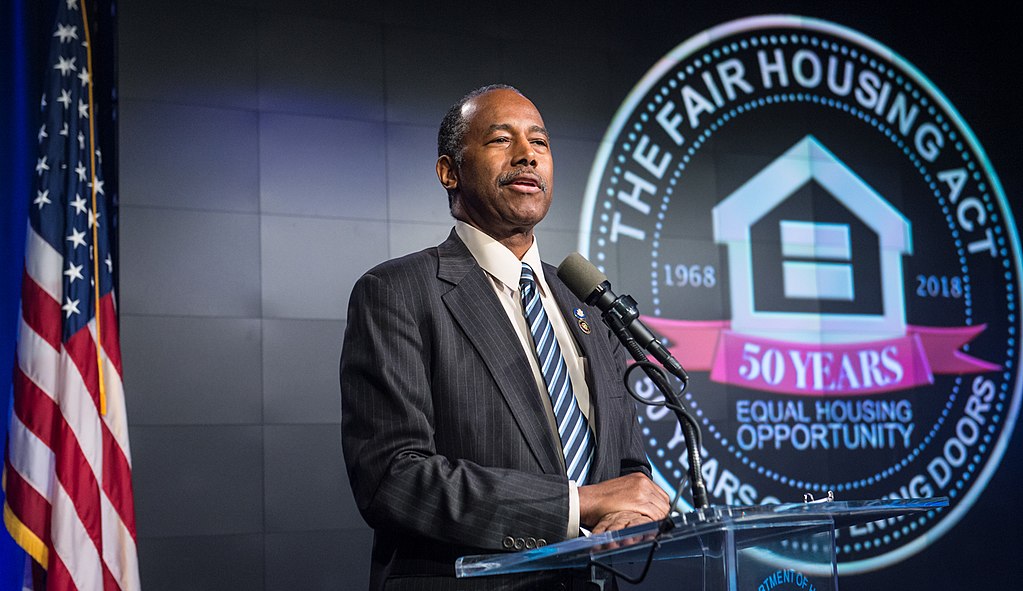

In the 1920s through the early 1940s, civil rights groups focused on litigation to solve housing problems. In the 1950s, visionaries like Morris Milgram proposed that racism and segregation would be outgrown if hearts and minds were changed, and in the 1960s, a combination of the previous tactics combined with direct action were the order of the day, culminating in the Fair Housing Act of 1968. And yet, as we learned especially during the Great Recession, African-Americans are still subject to unscrupulous and predatory mortgage lending, and white home ownership (and the associated wealth) still outpaces African-American home ownership. The idyllic view of the 1950s that racism was a mere illness that could be cured has been replaced by the more robust and muscular understanding that racism is a systemic problem, bound together by both race and class issues, and cemented in a foundation of white supremacy. Without the efforts of pioneers like Morris Milgram, however, the centrality of housing as a civil rights issue might have been discounted for a few more years; the idea that only whiteness could be equated with the middle class received a few chips in its facade as the Black middle class coexisted with their white neighbors; and even his failures illustrated the limitations of developers in the face of far stronger real estate and banking industries.

If there were simple solutions to these ongoing problems, the problems wouldn’t exist anymore. But there are ideas still to be considered, and the general approach was addressed by Hillary Clinton in 2016:

In the push for social progress, which comes first: changed hearts or changed laws?

Hillary Clinton answered this question in the course of her quasi-private meeting with activists from the Black Lives Matter movement, and she came down firmly on the side of the latter. “I don’t believe you change hearts,” Clinton told Julius Jones in an candid moment backstage after a campaign event. “I believe you change laws, you change allocation of resources, you change the way systems operate. You’re not going to change every heart. You’re not. But at the end of the day, we can do a whole lot to change some hearts, and change some systems, and create more opportunities for people who deserve to have them.” Source: Hillary Clinton’s Blunt View of Social Progress

In his later years, Milgram embraced a similar viewpoint:

Today it is clearer than ever that the only effective way to redress the structural inequities in housing wealth — which is most Americans’ wealth — would be through muscular policy. Milgram did make a move in that direction: with civil rights leader James Farmer, he set up the Fund for an Open Society, which offered mortgage incentives for people buying homes in interracial neighborhoods. In Good Neighborhood, he argued that developers of integrated housing and individual buyers on integrated blocks ought to get special FHA financing. Interestingly, as a 21st-century corollary, a law professor recently proposed restricting the mortgage-interest tax deduction to those who own homes in neighborhoods that are at least 10 percent black. Source: “Housing Is Everybody’s Problem”: The Forgotten Crusade of Morris Milgram

It’s clear that none of these needed changes will occur during this administration, and in fact, we may be taking more than a few steps backwards. But the ideas exist, and now and in the future, we must join together to use our voices to confront closed hearts and minds, while pushing our political leaders to implement incentive-based policies.

Morning meese…Thanks for another wonderful diary, Sher.

Jan…Wygal is having a problem when trying to sign in…It is saying this website is “not secure”.I don’t seem to be having the problem though….

I’ll check back later …Thanks Jan!

Here’s a screenshot of what she’s seeing…

http://motleymoose.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/wKQ5UMGY.jpg

Only thing that would make any sense is if for some reason the SSL for the Moose wasn’t up to date…

The Moose doesn’t run under SSL – the “https” version won’t render the pictures and the legacy pages properly for whatever reason so it should be run as “http”. On browsers, there is a lock with a slash through it, on personal electronic devices, you may get the warning. Since there is no sensitive information entered into the site it really doesn’t matter, more of an annoyance than anything.

I hope that helps!

{{{Batch}}} – I emailed Jan with this, just in case she checks her emails before reading the comments in here.

Hope your day goes well. moar {{{HUGS}}}

{{{Fitz}}}…Thanks for that…Kinda weird that WYgal is getting this and it looks like no one else is…Hope Jan can fix whatever the cause is

Hope you have a lovely day too… moar {{{Hugs}}}

Is it preventing her from coming here or is it just a scary warning/notification? SSL certificates are not entirely trouble – free.

I think it’s just a warning, basket but not sure. She didn’t say outright if it was preventing her from signing in. You might tell her that.

{{{DoReMI}}} – thanks for the work you’ve done on this series. And Hillary is right. She usually is. We have to have the power to change policy and laws, to allocate resources – we’ll pick up a few hearts and minds when we do that, we’ll never get all or even most of them. But it will change behavior and that will make a whole lot of things better for a whole lot of people. So first – get the power to change policy and laws, to allocate resources. Step by step. moar {{{HUGS}}}