![By Bryanmackinnon (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://motleymoose.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/HiglanderFolkSchoolCenter-HistoricalMarkerFront-1024x768.jpg)

The Highlander Center, one of the most important retreats for social activism, had a major fire over the weekend. It was one of MLK’s favorite places to decompress. https://t.co/JE6M86XuXt

— Ray Winbush (@rwinbush) April 1, 2019

Official statement from the Highlander Research Center about the fire in the early morning hours. Love and solidarity! #highlandercenter pic.twitter.com/uZ7MZSOdsh

— Kathryn Julian (@kjulian_history) March 29, 2019

I was organizing some files last night and came across the program for my daughter’s college senior [vocal] recital; today’s post has the same title as her recital. It inspired me to think outside of the box, so today I’m sharing information, not about a person, but about an institution that played a pivotal, but too often unmentioned-in-white-America, role in the civil rights movement, the Highlander Folk School. With such notable alumni as Septima Clark, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Rosa Parks, Ralph Abernathy, and John Lewis, it’s an institution worth highlighting.

Highlander Folk School (HFS) started in 1932, following the settlement house model (except in a rural setting) and serving as a community center. Area residents could borrow books from the HFS library; send their children for free music lessons or to attend nursery school; join the quilting cooperative or use the community cannery; and if you were a WPA worker, join the WPA union established by HFS. In the evenings, men and women could attend classes in psychology, cultural geography, revolutionary literature, and current political/economic topics.

At Highlander the purpose of education was to make people more powerful, and more capable in their work and their lives. Horton [ed. Myles Horton, co-founder of HFS] had what he called a “two-eye” approach to teaching: with one eye he tried to look at people as they were, while with the other he looked at what they might become. “My job as a gardener or educator is to know that the potential is there and that it will unfold. People have a potential for growth; it’s inside, it’s in the seed” (Myles Horton (1905–1990))

The emphasis on “what they might become” caused HFS to become involved in the labor struggles of the era, with explicit goals:

(1) serve as a community center for residents in the area based on ideas of unionism and cooperation; (2) develop a workshop program in order to train hundreds of Southern labor leaders; and (3) develop a field and extension program that would enable HFS staff to teach in other communities and in strike situations whenever requested. (“The Women of Highlander,” Langston, Donna in Women in the Civil Rights Movement, Vicki L. Crawford, Jacqueline Anne Rouse and Barbara Woods, eds., p. 147)

Study-intensives lasting from 4-6 weeks were held to teach and train labor leadership in everything from strike tactics to parliamentary law, while shorter workshops were held on single topics. Their efforts led to the CIO asking for HFS assistance in 1937 during its Dixie Drive, when the CIO attempted to organize all of the South. HFS acted as their de facto educational arm, a relationship which continued into the mid-to-late 1940s, until the leftist leanings of HFS became too uncomfortable for the CIO (the Taft-Hartley Act required union officers to sign an anti-Communist affidavit; HFS supported even those unions whose officials refused to sign). The leftist leanings of HFS were certainly not new or sudden; from its very beginnings, it had insisted upon a policy of equality and full integration.

One of the most controversial issues, one that continued to arise throughout Highlander’s period of working with the unions, was the matter of race. Although Highlander had had a policy of being an integrated institution from the time it opened in 1932, the unions had been very reluctant to actually sponsor integrated schools. It was not until 1944, when the United Auto Workers held an integrated session at the school, that a residential session involved both black and white members. Eating at a table together, sleeping in the same dormitory rooms, using the same bathrooms were very emotional subjects during this time. Some of the members went away feeling that they had been changed by their living experience while at Highlander, but others were not convinced about a place that openly condoned white and black living–and especially one that had as many “Yankee” visitors.

Its union experience forced the Highlander staff to think more clearly about the issue of race and its meaning for the future of the South. This was one of the turning points in Highlander’s history. (Fifty Years With Highlander)

Highlander began addressing issues of race relations and desegregation even before the 1954 Brown v Board of Education decision, holding workshops and developing curriculum and guides which could be used by organizers in their communities. Rosa Parks attended a workshop in 1955, just weeks before she refused to give up her seat. Septima Clark attended a workshop in 1954, and she returned later in 1954 for another workshop, bringing her cousin, Bernice Robinson, as well as Esau Jenkins. Jenkins returned to his home, Johns Island, SC, and ran for school trustee. He was defeated, but he was the first African-American to run since Reconstruction. Additionally, the trio persuaded HFS to fund a literacy school for adult African-Americans to prepare them to register to vote (and pass the literacy requirements). When the local principal and local churches were afraid to let HFS use their buildings, HFS gave Bernice Robinson an interest-free loan to buy an old school building, and pay for transportation, equipment, and supplies. Clark, a teacher, was instrumental in developing the curriculum for adult students, based on their life experiences, whether filling out a Sears mail order form, signing checks, or completing voter registration materials. In 1956, when Clark was fired from her teaching job (just four years shy of qualifying for her pension) for refusing to give up her NAACP membership, she was hired by HFS as their Director of Education. The Citizenship Education Program (CEP) continued under Clark’s leadership, and between 1954 and 1961, “HFS had 37 programs with over 1,295 participants.” (Langston, p. 157) The CEP trained the teachers; the outreach of the citizenship schools was broader and deeper than the CEP numbers indicate. The schools didn’t just prepare students to vote; they often became a mobilizing factor. Fannie Lou Hamer became a civil rights’ activist after attending a citizenship school; Andrew Young viewed them as the building blocks of the movement.

In a 1981 interview, civil rights leader Andrew Young commented, “If you look at the black elected officials and the people who are political leaders across the South now, it’s full of people who had their first involvement in civil rights in the Citizenship Training Program.” Informally known as Citizenship Schools, this adult education program began in 1958 under the sponsorship of Tennessee’s Highlander Folk School, which handed it over to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in 1961. By the time the project ended in 1970, approximately 2500 African Americans had taught these basic literacy and political education classes for tens of thousands of their neighbors. The program never had a high profile, but civil rights leaders and scholars assert that it helped to bring many people into the movement, cultivated grassroots leaders, and increased black participation in voting and other civic activities. (Levine, David P. “The Birth of the Citizenship Schools: Entwining the Struggles for Literacy and Freedom.” History of Education Quarterly, vol. 44, no. 3, 2004, p. 388. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3218028.)

The higher profile these activities afforded HFS also contributed to its downfall. The focus on civil rights rather than efforts on behalf of the local community diminished the strong support HFS had always enjoyed. Southern politicians worked to undermine HFS. In 1957, Dr. King was to give a keynote speech at a conference celebrating HFS’ 25th anniversary. Georgia’s governor arranged for the Georgia Commission on Education (a taxpayer-funded group which worked against desegregation) to send a photographer under false pretenses; the photographer had the goal of discrediting Martin Luther King by red-baiting and race-baiting.

Ed Friend had arrived in Monteagle with a letter of recommendation and introduced himself as a photographer, asking Horton if he could photograph and film conference events and participants. Horton quickly agreed, thinking he would buy some of Friend’s photographs for publicity purposes. As the weekend progressed, Horton thought it odd that Friend appeared uninterested in photographing or filming the speeches or meetings and more interested in the interracial socializing, the folk-dancing and swimming. And he always seemed to be trying to get Abner Berry [ed. registered for the conference as a free-lance writer, while in fact a columnist for The Daily Worker] into photographs. This irritated Horton. Horton wanted a photo of Martin Luther King, Jr., Rosa Parks, Aubrey Williams, John Thompson, and himself, but Friend insinuated Berry into the scene and snapped the picture… About a month later, the reasons for Friend’s behavior became clear.

Using the tapes and his own photographs, Ed Friend published a four-page, newspapersized broadside. The headline read, “Communist Training School, Monteagle, Tenn.” The text named the people attending the meeting and the organizations they represented. This broadside, despite its clumsy usage, was to become famous in the history of the civil rights movement.

From 250,000 to 1,000,000 of these broadsides were printed and distributed–at state expense-throughout the country.(“Are You a Communist?” Highlander 1957)

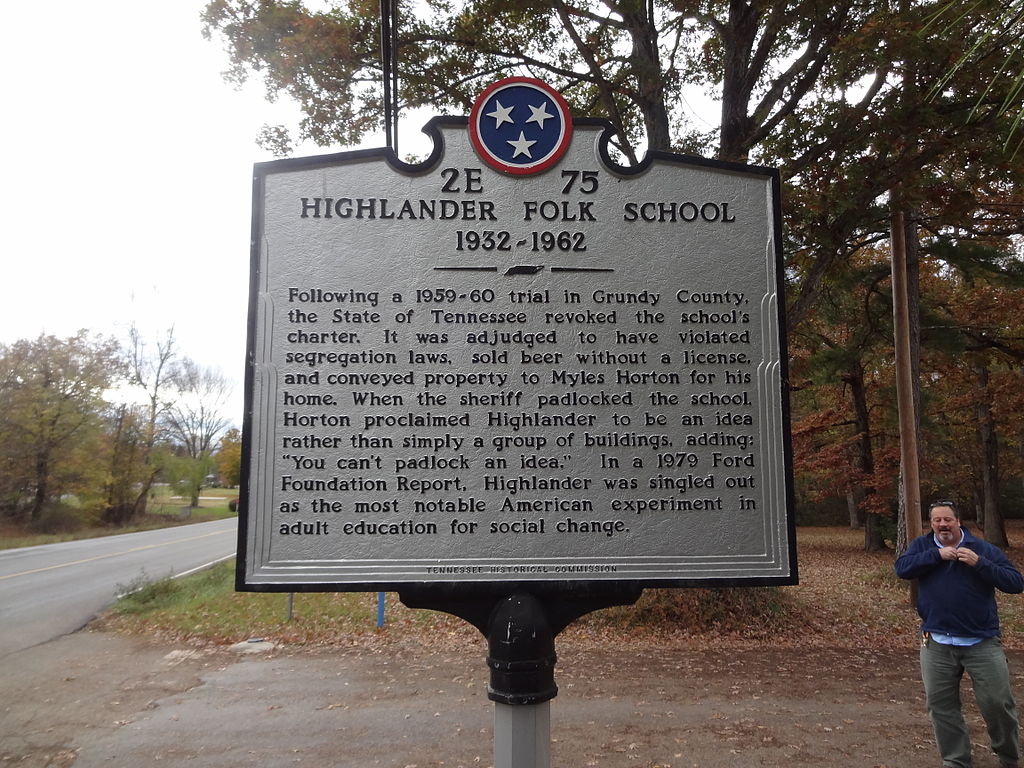

HFS survived the outlandish and damaging allegations, in part because it published a statement in the New York Times signed by prominent Americans, including Eleanor Roosevelt. The Tennessee legislature was more successful when it decided to investigate the “subversive” activities of HFS. A committee couldn’t find any evidence of Communist activity, but they did recommend that the district attorney general revoke the HFS charter, since they had integrated schools which were technically in violation of State law. A raid was conducted with prepackaged charges in place: solutions in search of problems. The charges included finding that Myles Horton was found drinking on the property (HFS was located in a dry county); Horton was in Europe for an adult education conference at the time of the raid. Accusations were leveled that black men and white women were found having sex in the library; the library hadn’t been built yet. Septima Clark was charged with illegal sale and possession of whiskey and with resisting arrest (she asked to phone a lawyer). None of those arrested were ever brought to trial, but HFS was declared a public nuisance and shut down pending a trial. The charges against HFS were that it sold beer and other items without a license; that Horton had operated the school for public gain; and the school had allowed blacks and whites to attend together, a violation of a 1901 TN law. The charges were trumped up, and the state’s witnesses were creative storytellers; it was enough for HFS to be found guilty. The judge ordered the corporate charter be revoked, and the property was liquidated and placed in receivership. Highlander never received any remuneration after its assets were sold.

![Bryanmackinnon [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]](http://motleymoose.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/HiglanderFolkSchoolCenter-HistoricalMarkerBack-1024x768.jpg)

The Highlander idea was not padlocked. The day after the charter was revoked, Horton took out a new charter for a new school, and the Highlander Research and Education Center was born and located in Knoxville, TN. In 1971, Highlander moved to New Market, TN, its current location. And despite the fire and the partial loss of Highlander archives, their commitment continues.

We are committed to being a catalyst for grassroots organizing and movement building at home in Appalachia and across the South.

We still believe in the power of popular education, language justice, participatory research,… https://t.co/xhUO2xFPDO

— Highlander Center (@HighlanderCtr) March 31, 2019

{{{DoReMI}}} – thank you for the information about/history of the Highlander Folk School/Research Center. I vaguely remember reading about it in various bios of Eleanor Roosevelt several years back but hadn’t carried it forward as it were. I’m glad they’re still alive and well if not actually in the same space and under the same name. And I’ll leave my speculations about the fire as just that – speculations. But history is rhyming way too much for comfort right now. sigh. Thank you again.

You are not alone in your speculation. Highlander is being very, very careful in their statements, but the very fact that they’re urging people to wait for the report from the fire department is a message in and of itself.