![Handelsman & Young [Public domain]](http://motleymoose.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/1024px-South_Bend_World_Famed-677x1024.jpg)

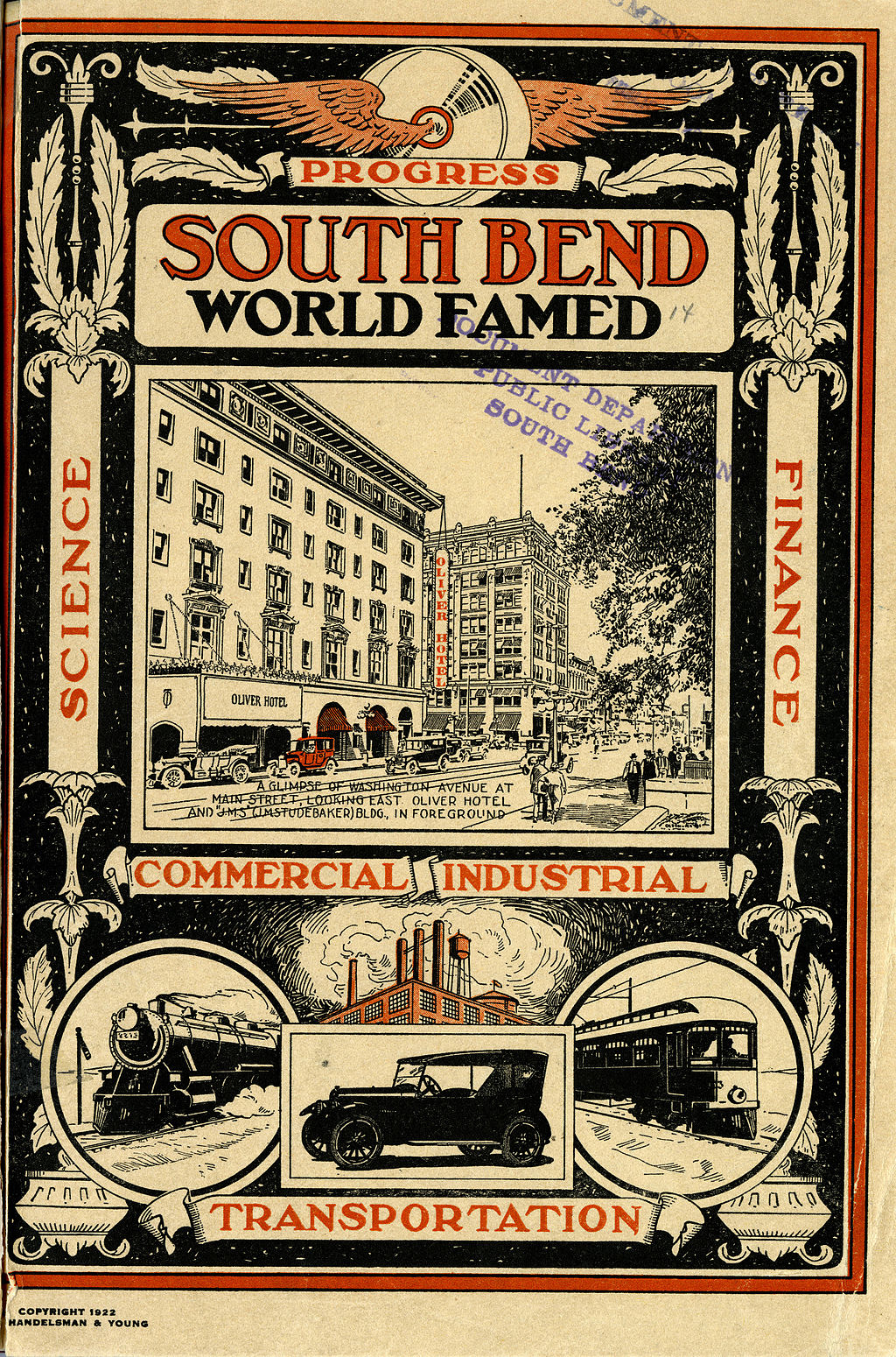

I do not have a long history of reading political memoirs. In 2008, I read President Obama’s Dreams from My Father and The Audacity of Hope after I had decided to support him; over the years, I have read several of Sec. Clinton’s books (although I still haven’t been able to read What Happened). However, when Pete Buttigieg started making noises about running for president, I immediately downloaded his book to read. I’ve been following his career for years, solely because my German immigrant great-grandparents settled in South Bend in the 1890s, and the home they were finally able to purchase is still in my family. I want South Bend to succeed and prosper, and when a young, charismatic mayor was elected, I started paying closer attention to the city and the mayor. I had been aware of the barest-of-bones details of Buttigieg’s life: Harvard grad, check; Rhodes Scholar, check; youngest elected mayor of a city of at least 100,000, check. I hadn’t realized he grew up in homes less than five miles from my family’s home, or that both of his parents taught at Notre Dame (from my family’s perspective, South Bend is not a university town in the same sense that Ann Arbor is; due to my family’s history, South Bend is and will always be the town that Studebaker built), or even that Mayor Pete’s coming out was after he was elected to office, not before. Buttigieg’s memoir covers the autobiographical elements of his life in a mostly-cursory way and devotes much of the pages to his governing philosophy and the practical governing results in South Bend. That’s the reason for reading books like this, as far as I’m concerned. The autobiographical tidbits provide context, but the nitty-gritty is in the details the memoirist chooses to share. Those details reflect their priorities and the narrative they wish to forge. It’s up to the reader to determine if the narrative is an honest assessment or more weighted towards promoting a political agenda. After reading Buttigieg’s book, I can only say I’m more confused than convinced; more conflicted than persuaded; and more skeptical than converted.

Did preconceived opinions of this person change after reading their story? If so, did it change for the better or the worse? Explain.

This should be an easy question, but I’ve struggled with an answer because the release of the book so closely coincided with Buttigieg’s town hall and subsequent barnstorming; it’s difficult to separate Book Pete and Campaign Pete at this point. I had a favorable opinion of Mayor Pete before reading his book, and the book by itself did little to alter that. Although I think there are limits to his data-driven approach to governance, his rationale for using that approach is an interesting statement about his understanding of leadership:

…using data in a transparent way exposes leaders to the vulnerability of letting people see them succeed or fail. Being vulnerable, in this sense, isn’t about displaying our emotional life. It has to do with attaching your reputation to a project when there is a risk of it failing publicly. The more a policy initiative resembles a performance where people are eager to see if the performer will succeed, the more vulnerable–and effective–an elected leader can be. …The possibility of highly visible failure has an exceptional power to propel us to want to succeed, and that power can be harnessed to motivate a team or even a community to do something difficult. (pp. 160-161)

Buttigieg makes this argument before launching into the story of one of his most visible initiatives as mayor of South Bend, the fixing or demolition of 1000 houses in 1000 days. The metric was established as a means of dealing with a massive backlog of substandard housing, blight, and the downward population trend in South Bend; the metric was intended to cut through “analysis paralysis” and create a sense of urgency, vulnerability, and accountability. South Bend achieved its goal and then some: more than 1100 homes were removed from the vacant and abandoned list, either through repair or demolition.

In a vacuum, or if one is just reading the book, this all sounds admirable and impressive. However, even as I was reading about the “right-sizing” plan for South Bend, my first thought was, “If not handled carefully, this is a prescription for gentrification.” (It’s an issue I’m particularly sensitive to, as I watch the resurgence of Detroit and the gentrification that is occurring here.) It led me to do further research, and what is untold in Buttigieg’s book is that the approach did come under criticism and ongoing efforts to combat blight have had to be adjusted after complaints of a heavy-handed approach which was not readily responsive to the needs and concerns of residents. His avoidance of addressing this issue in the book is cause for concern for me. I don’t think Buttigieg is a racist; I do have serious questions about his level of awareness about his own privilege and what I see as a tendency to hand-wave at issues of race. Combined with the observations by some (including by me) that Buttigieg is currently centering the white working class in his campaigning, I find myself with a less-favorable view than I held before I read the book.

How does the author approach his own story? With a sense of irony, sympathy, distance, comedy, or something else entirely?

Buttigieg is smart, engaging, funny, and charming, and all of that comes across clearly in his book. He is also a self-described introvert and intensely private; it’s these characteristics which define Buttigieg’s approach to his story, whether it’s conscious or not. Throughout the book, I felt as if the Buttigieg being presented was Buttigieg-at-arm’s-length. I got impressive insight and analysis about the role of tech-oriented governance; the challenges of balancing data, responsiveness, and efficiency; and even a soaring justification for the politics of moving forward rather than looking back. But throughout the book, I felt I was getting a glimpse of Pete’s Head, but never Pete’s Heart. Is that important or necessary? I think it is. I don’t need to know his deepest emotions; I do like to know what drives and motivates, and beyond data and wonkishness, I’m not sure I learned that.

Were there any parts of the book/their life where you would have liked more information?

Because this is written as a political memoir, the focus on policy and programs is understandable, but I kept looking for the people stories that explained what makes Buttigieg tick…the favorite teacher, the conversations with South Bend constituents, the interactions with soldiers and citizens in Afghanistan. There are moments detailed, but they are stories told within the context of data or achieving policy goals. I’ve come to the conclusion that the best way to decipher Buttigieg is to follow his husband on Twitter. It’s not going to come from Mayor Pete himself.

Beyond that, Mayor Pete’s campaign calls to empathize and connect with the left-behind Midwesterner are couched in very different terms in the book than on the trail. In the book, he disparages the inherent call to look back found in MAGAgain; that coal jobs aren’t coming back any more than Studebaker is coming back to South Bend and that we don’t want to go back.

Especially in this moment, when “make great” is the mantra of a backward populist movement, the word seems associated with the worst in our politics, its champions consumed by a kind of chest-thumping that seeks to drown out any voice that would point out the prejudice and inequality we still must overcome. (pp. 306-307)

This is not the same Mayor Pete I’m hearing on the campaign trail, and I’d like more detail so I can understand which is the authentic Pete Buttigieg.

What’s the author’s most admirable trait? Is there any way in which you wish you resembled the author?

Buttigieg is an effective communicator; even as sections of his book take on a Joycean stream of consciousness narrative mode, he clearly and effectively gets his point made. He never appears to be intentionally engaging in persuasion and yet he’s very persuasive; he never appears to be intentionally selling anything, and yet I found myself fascinated by the concept of smart sewers (another one of his signature achievements for South Bend) and ready to advocate for similar systems throughout the Midwest. Sadly, it’s this very strength which is leading me to conclude that the Pete Buttigieg I’m seeing on the trail knows exactly what he’s saying and how he’s being interpreted by supporters and non-supporters alike.

Why do you think the title was chosen for the book?

This is explicitly explained by Pete in the book. The title is derived from a quote from Buttigieg’s favorite book, Ulysses by James Joyce. The quote is, “Think you’re escaping and run into yourself. Longest way round is the shortest way home.” Although he acknowledges that it, to some degree, explains the arc of his own life before he returned home, he also uses it to describe his core political philosophy; that “I’ve learned that great families, great cities, and even great nations are built through attention to the everyday.” (p. 310)

Thanks for this very fine analysis, DoReMI. Found it most interesting. I do think Mayor Pete’s primary drawback is his unacknowledged white male privilege.

All I know is that after reading about him I remain unmoved—so far. Haven’t heard him speak.

I would never ever have expected Campaign Pete after the little bit I followed him in past years and based on his book. It may be that he’s engaging in a cynical, pandering ploy to garner attention and white voters; he’s certainly smart enough to be able to dog whistle while leaving plausible deniability. But the bottom line for me is that no matter what the motivation, he’s shown me who he is. And I don’t like it.

{{{DoReMI}}} – I seriously appreciate that you’re doing the reading (so I don’t have to). I don’t really read “candidate books” although I’ve read books by candidates I like some of which were policy books. I’ve definitely read most of Bill & Hillary Clinton’s books. Until What Happened – I’m still stuck about 40 pages in. Mayor/Mayo Pete never impressed me – but then I hadn’t even heard of him until he started campaigning for president and there’s certainly nothing in his campaigning that would make me consider him at all. He’s just one more white male dogwhistling the racists to bring them back to a diverse party that doesn’t want them. Of course people who just look at twitler and not the very large and nasty machine that put him in the WH would think “oh hell, even I can beat that” – but anyone who isn’t looking at that large and nasty machine doesn’t have the chops for the job anyway.

Thank you again – & I’ll try to get over to Orange and read Janesaunt’s book report. {{{HUGS}}}