“You know you’re the only one of us who can do this.” Gerald Holloway, the chief of the prehistoric archaeological team, was speaking.

Grace Ling nodded. She was barely five feet tall, had trouble eating enough to maintain her weight at one hundred pounds, and was as fit as she could be after a regime that included weight-lifting, five-mile daily runs, and twice-weekly karate sessions.

“The space is ten inches high,” Holloway continued. “No room for a backpack—it would get crushed, so you’ll have to carry everything in your side pockets. We don’t know how long the passage is. When you come to the end, we hope you’re going to find bones, tools, something.”

Grace took a deep breath. “I’m up for it.”

Success would ensure funding for future prehistoric archaeological expeditions, from which archaeologists might discover more about preliterate societies. She might even be chosen to lead an expedition herself one day.

Three days later she was ready. On her head she wore a close-fitting steel helmet with a headlamp. Her arms, core, and legs were encased in sturdy denim. Thick gloves covered her hands and kneepads protected her knees. In the zipped pockets on the sides of her overalls were a personal emergency device, emergency rations, flashlights, batteries, a medical kit, and water pouches. She even had a couple of candles and matches tucked away. She wore goggles and a dust mask hung around her neck, ready to put on when she needed it.

Mindful of the fact that her cell phone didn’t work in the underground garage of her apartment building, Grace had insisted on a low-tech safety precaution, a thin but flexible nylon rope tied around her left ankle. What if the emergency device failed? Or her headlamp?

“Surely they didn’t have to crawl through this tiny opening to get into the cave, did they?” she wondered aloud.

Holloway shook his head. “This tiny opening resulted from an earthquake or a rockfall, probably thousands of years ago,” he said. “The climate would have been much colder then, and life would have been very hard. Most of these ancient humans died before the age of forty.”

“You know the drill, right?” Tony Everton, the team medical officer spoke. “You’ll be alone and in the dark except for your lamp. Let’s hope it doesn’t fail while you’re crawling through the passage. After five or ten minutes you’ll become so disoriented you won’t know whether down is up or up is down. You may slip into an altered state of consciousness.”

”Gee, thanks for the pep talk, Tony.” What was the man trying to do, Grace thought, scare her to the point where she’d refuse the mission?

“I’m ready,” she said with a confident toss of her head and dropped to her hands and knees. The large spool of nylon rope sat close to the passage entrance. Since her hands were covered with thick gloves, Tony adjusted the dust mask over her nose and mouth.

At first it wasn’t so bad: excitement kept her going. With heart pounding, she crawled forward, inches at a time. The passage smelt musty but thankfully, not of guano. The team, which had sunk cores into the passage as well as the cave and analyzed the contents, assured her there would be no bats or bat dung. Then it began getting to her: the thought of tons of rock overhead, ready to crush her if something disturbed the hillside. And it was so dark. Her headlamp illuminated only a few inches in front of her. When would she reach the end of the passage?

What had possessed her to volunteer for this mission? Would there be enough air? Would she die here? Why, why, WHY had she done this? What if she passed out and no one knew? What if she never recovered consciousness and died? Sweat broke out inside her goggles so they misted over, broke out under her thick layer of clothes. She could feel the sharp points of rocks through her heavy gloves and kneepads. How much longer? HOW LONG?

If she lived through this mission she’d never, ever go back into the earth again.

Then she felt a current of air. Air! The darkness was still total and terrifying beyond her headlamp, but the passage was widening. Soon she could lift her head, then her shoulders. Then she could wriggle free of the passage and get to her hands and knees. Then she stood up—shakily, because of her cramped limbs and the rope around her ankle, but up.

She was in the cave.

____________

When Au’Ri entered the cave, she found that Rig, her mate, had already prepared the wall for her and smoothed the earth of the cave floor with a tree branch. Her torch was smoky and did not shed enough illumination, so she used it to light one of the grease lamps that enabled her to see a bigger area. Although outside the cave it was summer, the season of plenty, inside the cave it was so cool she was glad of her hide tunic, her leggings, and above all, the warm boots trimmed with fur that protected her feet from the cold floor beneath.

Au’Ri was a woman of twenty summers. As the tribe’s shaman, she had been tasked to appeal to the Great Spirit to protect the tribe’s source of food. She would accomplish this by drawing what she had seen from her hiding place outside on the hill, a hunting scene of great danger and even greater importance.

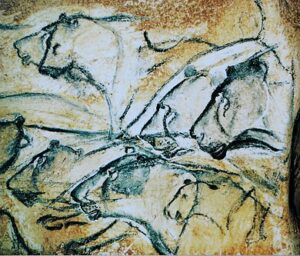

She measured the cave wall with her eyes, deciding where each part of the drawing should go. Then she took up her burin, an engraving tool of carefully flaked stone, to sketch the outline. Later she would use charcoal to outline the animals, and add color as needed to show the types of animals they were. Horses, ibex, cave lions, but not reindeer. Never would she depict reindeer, the sacred animal on which her tribe depended for food, for hides, for fat to burn for light, and for many other uses.

Au’Ri worked as long as the lamplight lasted, only then lighting the torch again and leaving the cave to drink, eat, and rest. All during the summer, while outside the rock shelter that was her tribe’s home the children laughed, played games, and made music by blowing into bone flutes; while some of the tribe gathered berries and herbs and dried them in the sunlight, and others smoke-dried the strips of reindeer meat that would let them survive the glacial winter, the scene she was painting on the wall took shape. Outside the cave, Rig gathered the lumps of soft rock and ground them into powder in hollowed-out sandstone. After he mixed the colors—white, black, brown, orange, and yellow—with animal fat, Au’Ri took them into the cave, working by lamplight with twigs, pointed slivers of bone, and even her fingertips to create the scene she’d visualized.

Finally, at the time of the Fall of the Leaf, she finished the painting. Holding up a lamp, she surveyed her masterpiece and sent up a silent prayer to the Great Spirit, the force that would see to it that cave lions would prey only on the herbivores depicted, and not the sacred reindeer.

“Please protect the reindeer herds, Great Spirit of All, and send us food.”

She smiled as she contemplated the painting, then dipped her left hand in a container of red color and held it high up against the cave wall. It was her signature, her way of saying, “This is my work. This is due to the hand and eye of Au’Ri.”

A little voice spoke by her side. “Ma-ma, lift me up!”

Au’Ri looked down at Na’Cia, her daughter of five summers, who was holding up her arms. Smiling, she dipped the child’s hand into the red color, then hoisted Na’Cia onto her shoulders. She leaned forward slightly while her daughter pressed the imprint of her little hand on the wall.

It was time to go. Au’Ri picked up the bundle of juniper and birch twigs tied together with a piece of sinew, and lit it from the lamp. Then she blew out the lamp and took her daughter by the hand. Together they walked out of the cave, away from the painting that no one else would see for twenty thousand years.

______________

Surprisingly, the air in the cave was fresh and cool, but Grace’s goggles were still fogged up. She stripped off her heavy gloves, dropping them on the floor of the cave. She reached into one of the zipped pockets on her sleeve, extracted a handkerchief, and wiped the goggles dry. Then she removed a flat flashlight from another pocket on the side of her overalls and switched it on.

She gasped. The scene on the white calcite wall of the cave showed a mass of horses and ibex fleeing before three cave lions. The wildly rolling eyes of the horses and ibex, the high leaps of their gallops, showed their terror. The cave lions’ open jaws, their sharp teeth, and their focused gaze showed how determined they were to bring down the animals they were chasing.

The scene had been painted on ripples in the cave wall, so the horses, ibex, and cave lions appeared to be actually moving. The golds, reds, browns, and blacks used showed as clearly as the day they were painted. Over millennia, rain seeping into the limestone cave had created a glaze that would preserve the paintings from everything except human breath and human behavior.

As her flashlight moved slowly from the black-spotted gold faces of the cave lions to the faces of the brown, black, and gray horses and ibex, she could almost hear the frightened neighs and bleats of the herds, feel the vibration of their thundering hooves. Then her flashlight moved up high on the wall, to the left of the painting, picking out the red handprints. The sight of the larger handprint, then the smaller one, made Grace fall to her knees and sob as emotion overcame her. In that instant she became one with the artist who had lived so many thousands of years ago, one with the child, whoever it had been, who’d made that tiny handprint. After her sobs stilled, she dried her eyes and became the prehistoric archaeologist again.

Shakily, she removed the tweezers and scrapers from various pockets, along with several plastic bags. She picked up the lumps of rock and blackened bone, stowed them in the plastic bags, sealed them, and put them back in the pockets. She took as many photographs as she could with the flat, battery-powered camera, then reached down to yank the cord on her ankle. She was going back now, back through the passage. Yanking the ankle cord would let the team know she was on her way—and she felt the answering tug.

She must not fail in her mission. She had to tell the others what she had seen. Grace crawled through the darkness, slowly but with determination. It was becoming hard to breathe again. Oh, how she would rejoice if she lived through this journey up to the surface! Oh, how she’d celebrate when she was out! She’d breathe, breathe, breathe. She’d stay in a hot shower for an hour. She’d never, ever undertake a mission like this again.

She had to keep going. Inch, inch, crawl, crawl. Was it getting easier to breathe? Was the passage beginning to slope upward? Oh, how she wanted to be out!

Air. More air, the current blowing through the opening to the surface. A little light, then more. Now she could lift her head. Now she could see out, see the eager faces of the team waiting for her, their arms outstretched.

“Grace, what did you see? How do you feel? What did you find? Did you bring anything back?” The questions from the other team members came thick and fast.

Gerald and Tony helped her rise to her feet. She ripped off her gloves, goggles, and pollen mask, divested herself of the rope, and looked around at her teammates.

“I have seen a work of genius!” she said. “A magical working! In my whole life I’ve never felt so humble or so awestruck!”

As she handed her camera and the artifacts in her pockets to the other members of the team, Grace realized that she, Grace Ling, was not the same person who had crawled through the passage to the cave. The revelation of the cave painting, the difficult passage out to the world again, felt like a rebirth. She was conscious of the life force that connected her to every being who had ever lived—or ever would live—on Earth, from the beginning of time until time’s end.

The End

{{{Diana}}} Your Grace is a braver person than I am. There’s no way you’d get me into a tunnel like that. I’ve been in a cave a few times and won’t do that again either. When they turned out the lights so folks could tell what deep inside a cave is live, the dark felt like a weight on me as heavy as the rock itself. But yes, the cave paintings are glory itself. And anyone who actually pays attention to what they’re seeing will, like Grace, be changed.

Thanks for reading and commenting, dear bfitz!

Agree, I would be changed if I were to see such a thing. That’s why I subscribe to Archaeology Today. People who lived long, long ago fascinate me. They weren’t stupid: they just didn’t have electricity.

Thank you for posting this, Diana! I will return to read when I have an uninterrupted block of time.