Last week I mentioned that I was reading a book on the history of lynching, which resulted in more than a few folks expressing trepidation about my next post. Fear not! The post is here, and I should point out that technically, the book, On the Courthouse Lawn: Confronting the Legacy of Lynching in the Twenty-First Century by Sherrilyn Ifill is not a history as much as it is a call for restorative justice. In her 2007 book, she focuses on two lynchings and several averted lynchings which occurred on the Eastern Shore of Maryland during the 1930s, as well as numerous references to lynchings elsewhere in the country. Today’s post, using her book as a template, will focus on white silence and complicity then, the ongoing impact of that silence, and what reconciliation can look like.

Last week I mentioned that I was reading a book on the history of lynching, which resulted in more than a few folks expressing trepidation about my next post. Fear not! The post is here, and I should point out that technically, the book, On the Courthouse Lawn: Confronting the Legacy of Lynching in the Twenty-First Century by Sherrilyn Ifill is not a history as much as it is a call for restorative justice. In her 2007 book, she focuses on two lynchings and several averted lynchings which occurred on the Eastern Shore of Maryland during the 1930s, as well as numerous references to lynchings elsewhere in the country. Today’s post, using her book as a template, will focus on white silence and complicity then, the ongoing impact of that silence, and what reconciliation can look like.

Bare essentials

1. The Merriam-Webster definition of lynching is “to put to death (as by hanging) by mob action without legal approval or permission”.

- Although sources vary, most estimate that nearly 5000 black Americans were lynched between 1890 and 1960.

-

“There is no record of any white person ever having been convicted of murder for lynching a black person–not in the thousands of instances of white-on-black lynchings in thirty-four states.” (Ifill, p. 73)

-

Restorative justice is needed, “But merely providing victims and their descendants the opportunity to tell their stories is not enough. The stories must be heard. It is in the telling and hearing of formerly silenced stories that communities can re-create themselves.” (Ifill, p. 133)

Going beyond the dictionary definition

Most of us, especially those of us who are white, hear the word, “lynching” and conjure up images of a black man hanging from a tree. Some of us have even seen the old postcards which show crowds of white people posing in front of a tree where the victim still hangs. As horrific as that mental (and actual) image is, it is still far more antiseptic than the reality. What gets lost when reading things like the Merriam-Webster definition is that lynching was a tool of terror readily used by white supremacists in a white supremacist society.

Southern states were equipped with readily-available, fully-functioning criminal justice systems eager to punish African American defendants with hefty fines, imprisonment, terms of forced labor for state profit, and legal execution. Lynching in this era and region was not used as a tool of crime control, but rather as a tool of racial control wielded almost exclusively by white mobs against African American victims. Many lynching victims were not accused of any criminal act, and lynch mobs regularly displayed complete disregard for the legal system. (LYNCHING IN AMERICA: CONFRONTING THE LEGACY OF RACIAL TERROR)

Lynching, more often than not, involved mobs dragging the victim through the streets; beating, torturing, and mutilating them while they were still alive; the actual hanging; burning the body afterwards; and leaving the body for display…quite frequently in areas that black residents, and even black schoolchildren, were known to pass by. The goal of a lynching was not just some twisted version of justice, handed out by a mob intent on acting as judge, jury, and executioner. Nor was it merely a cruel, sadistic, horrific act carried out against a lone African-American victim. Lynching was intended as a warning and a silencing of entire African-American communities; it was a reminder that if they “stepped out of place,” they, too, could suffer the same fate.

White complicity, white silence

The thousands of African Americans lynched between 1880 and 1950 differed in many respects, but in most cases, the circumstances of their murders can be categorized as one or more of the following: (1) lynchings that resulted from a wildly distorted fear of interracial sex; (2) lynchings in response to casual social transgressions; (3) lynchings based on allegations of serious violent crime; (4) public spectacle lynchings; (5) lynchings that escalated into large-scale violence targeting the entire African American community; and (6) lynchings of sharecroppers, ministers, and community leaders who resisted mistreatment, which were most common between 1915 and 1940. (LYNCHING IN AMERICA: CONFRONTING THE LEGACY OF RACIAL TERROR)

Because lynching was a terroristic weapon of white supremacy (and the corollary belief that the African-American is sub-human), factors like evidence, proof, and proportionality were supplanted by rumor, hearsay, and the desire for retribution.

In 1889, in Aberdeen, Mississippi, Keith Bowen allegedly tried to enter a room where three white women were sitting; though no further allegation was made against him, Mr. Bowen was lynched by the “entire (white) neighborhood” for his “offense.”

General Lee, a black man, was lynched by a white mob in 1904 for merely knocking on the door of a white woman’s house in Reevesville, South Carolina.

White men lynched Jeff Brown in 1916 in Cedarbluff, Mississippi, for accidentally bumping into a white girl as he ran to catch a train. (LYNCHING IN AMERICA: CONFRONTING THE LEGACY OF RACIAL TERROR)

The public spectacle lynchings, the type we most often hear of today, are defined as

Public spectacle lynchings were those in which large crowds of white people, often numbering in the thousands, gathered to witness pre-planned, heinous killings that featured prolonged torture, mutilation, dismemberment, and/or burning of the victim. (LYNCHING IN AMERICA: CONFRONTING THE LEGACY OF RACIAL TERROR)

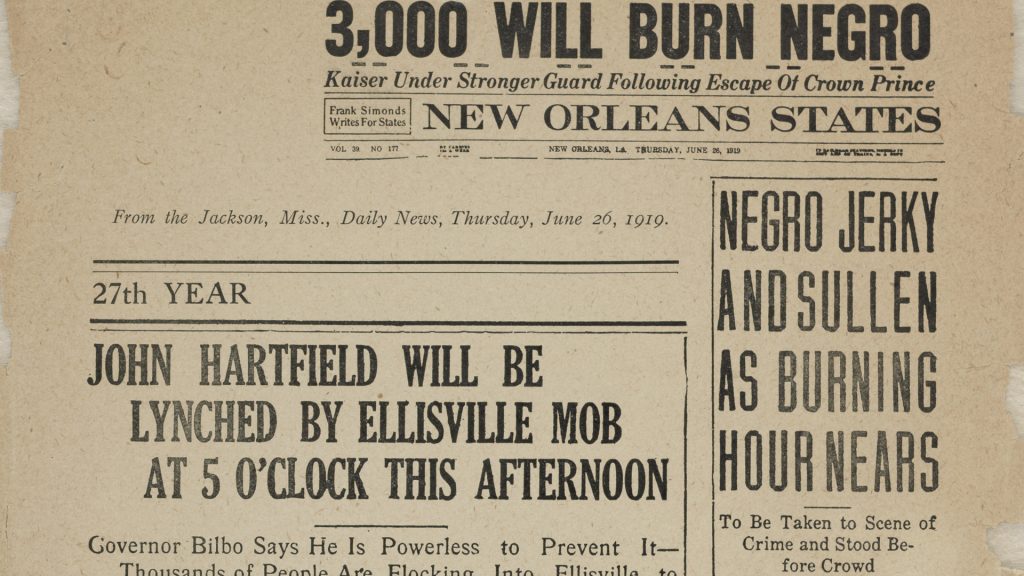

Read that definition again, slowly. Note the word “pre-planned.” Lynchings are often viewed today as some sort of out-of-control mob action, when in fact, in many cases they were orchestrated, planned events with dates and times announced in advance in order to allow the “public” to gather. In one lynching in Salisbury, MD in 1931, the crowd of spectators was estimated to be 1000, 10% of the white population of Salisbury; in a 1933 lynching in Princess Anne, MD, 2000 people witnessed the lynching, 20% of the white population at the time. In an era before cell phones and social media, and when even the telephone was a luxury, those types of numbers don’t materialize without some level of organizing.

As Sherilynn Ifill points out,

The willingness of lynchers to act publicly is tremendously significant. It reflects the lynchers’ certainty that they would never face punishment for their acts. The willingness of the crowd to participate in lynching–to cheer, to yell their encouragement, or just to stand and watch without intervention –is perhaps equally terrible. (Ifill, p. 58)

Pictures from lynchings make painfully clear that the white crowds at lynchings were not the “dregs of [white] society” but instead a cross-section. Although largely made up of white males, a quick perusal of the photos makes it clear that women and children were spectators too. In some cases, children were encouraged to be active participants. Describing some of the milder incidents (there are far, far worse examples, sometimes of children being coerced and other times as willing participants), Ifill notes:

Children were also present at the lynchings. A young boy was hoisted up to throw the rope over the bough of the tree on which Matthew Williams was hung. One witness to the lynching was most startled by the number of women and children in attendance. A young girl who tried to turn away from the burning body of George Armwood was scolded by her mother and compelled to watch Armwood “being barbecued.” (Ifill, p. 59)

White complicity, whether passive or active, in lynchings did not stop after the lynching was completed. Per Ifill,

Whites, for different reasons, also joined a conspiracy of silence. In silence there was safety–safety from potential prosecution for the lynchers, yes, but more important, safety from the danger of facing a difficult truth: that the quiet, close-knit little town that regarded itself as Christian and its residents as civic-minded and neighborly also could be bestial, cowardly, and lawless. (Ifill, p. 62)

In the two lynchings detailed by Ifill, the silence was called for explicitly by newspapers and by white church leaders, whether as a civic duty and an expression of regional loyalty, or as a way to protect the parishioners because “the community had suffered a strain.” (Ifill, p. 62) In the aftermath of the lynching of Matthew Williams in Salisbury, MD, a grand jury was held to investigate and called more than 100 witnesses; none of those witnesses could identify members of the lynch mob. In 1933, a grand jury investigating the George Armwood lynching issued no indictments, despite having sworn testimony from state police officers who identified nine men as the leaders of the lynch mob.

This silence was hardly limited to the Eastern Shore of Maryland, even when the Federal government got involved:

In February 1898, a white mob in Lake City, South Carolina, set fire to the home of the Baker family and riddled it with gunshots, killing Frazier Baker and his infant daughter, Julia, and leaving his wife and five surviving children wounded and traumatized. Baker, a black man, had aroused the hatred of the predominately white community when President William McKinley appointed him to the position of local postmaster. After efforts to have Baker removed from the post failed, local whites resorted to mob violence. The murder prompted a national campaign of letter-writing, activism, and advocacy spearheaded by Wells and others, which ultimately persuaded President McKinley to order a federal investigation that resulted in the prosecution of eleven white men implicated in the Baker lynching. Despite ample evidence, an all-white jury refused to convict any of the defendants. (LYNCHING IN AMERICA: CONFRONTING THE LEGACY OF RACIAL TERROR)

Why tell the stories now?

Even as I have skimmed over and elided the powerful, ghastly details of lynching, I have done so with this paragraph ringing in my ears:

The real challenge of truth-telling is the willingness to engage with fellow community members in the hard work of constructing a new community based on a full accounting of the past. The “new community” is one in which formerly excluded stories become part of the history, identity, and shared experience of all of the residents. At its core, reconciliation is just this: the creation of a new community…of both victims and perpetrators, of beneficiaries and bystanders. (Ifill, p. 133)

The silence that occurred in white communities immediately after a lynching has crossed generations and is still happening today. Some insist that it’s history, and since they were not directly involved, it has nothing to do with them; that any discussion of lynching as just dredging up the past for no good purpose. Others fear being put on the defensive or that they may be compelled to take responsibility for actions they knew nothing about; the “not all white people” claim, the “I don’t see color” assertion, and the “Can’t we all just be human beings?” question are the reflexive responses used to maintain the silence that protects the white person and denies any collective responsibility.

In her book, Ifill shares an anecdote about meeting with an historical society guide (“Parker”) who shared the story about a presentation made by a local professor (“Stewart”):

Parker stated that he had attended this gathering of the Historical Society, and what he described sounded like a very unpleasant and hostile meeting. Stewart presented her research describing the lynching of Matthew Williams in 1931. When she had finished, Stewart’s presentation was met with icy silence…Stewart, he [Parker] said, should just have presented the facts of what happened and not tried to assign blame or to interpret the events as indicative of the attitude of whites in the county. He and others like him saw the lynching as an aberration, a foul act committed by a few marginalized whites who may have been from out of town. Stewart treated the lynching as a kind of defining racial event for Salisbury and seemed to put the responsibility for the lynching on all whites. (Ifill, pp. 137-138)

As a white person, I can attest to hearing this sort of argument (or a variation on the theme) over and over and over again. Attempting to explain that personal lack of involvement does not change the fact that I have been a personal beneficiary of an oppressive, violent regime that dehumanized, and continues to dehumanize, generally results in more denial and more bluster. (Lately I’ve been able to make some headway with All-Lives-Matter types by using 9/11 as a broad comparison, i.e. If we remember what we were doing when the terror attack occurred, why do we expect the Black community to forget the terror used for generations against them?) I can only imagine the frustration, distrust, and anger that these sorts of denials evoke in those who have been oppressed. As important and necessary as those individual conversations are, they also point to the role that community restorative justice could play in creating spaces for conversations that go beyond the individual and examine the systemic.

What would restorative justice look like?

For the purposes of this post, I am going to highlight two public spaces which contribute to restorative justice by enabling truth-telling and conversation. The first is new and is more accurately two spaces, a museum and a memorial; the second is older and smaller, but no less important for its community. I will be focusing on the mission and purpose of each site, rather than the specifics of the memorials, which can be found at the provided links.

The Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) has been the moving force behind both The Legacy Museum and The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, both located in Montgomery, AL and opened in April. Located less than a mile from each other, the museum and memorial have two distinct, but complementary functions. The museum is a data- and information-based educational center:

EJI believes that the history of racial inequality and economic injustice in the United States has created continuing challenges for all Americans, and more must be done to advance our collective goal of equal justice for all. The United States has done very little to acknowledge the legacy of slavery, lynching, and racial segregation. As a result, people of color are disproportionately marginalized, disadvantaged and mistreated. The American criminal justice system is compromised by racial disparities and unreliability that is influenced by a presumption of guilt and dangerousness that is often assigned to people of color. For more than a decade, EJI has been conducting extensive research into the history of racial injustice and the narratives that have sustained injustice across generations. Our new museum is the physical manifestation of that research. (The Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration)

The memorial’s purpose is primarily educational and encourages contemplation and remembrance, but also has a unique outreach initiative.

The memorial structure at the center of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice is constructed of over 800 corten steel monuments, one for each county in the United States where a racial terror lynching took place. The names of the lynching victims are engraved on the monuments. In the six-acre park surrounding the memorial is a field of identical monuments, waiting to be claimed and installed in the counties they represent. Over time, the National Memorial will serve as a report on which parts of the country have confronted the truth of this terror and which have not. (EJI’s Community Remembrance Project)

The oldest lynching memorial in the United States is located in Duluth, MN and was dedicated in 2003. The Clayton-Jackson-McGhie Memorial commemorates “…the evening of June 15, 1920, three black men, wrongly accused of raping a white woman, were abducted from the Duluth, MN, City Jail. A mob numbering between five and ten thousand people savagely beat and tortured these three young men, then hanged them from a lamppost in the middle of Duluth’s downtown.” (The Story)

The purpose of the Committee initially was to facilitate the placement of a permanent memorial marker at the site memorial where three young African-Americans were lynched in Duluth on June 15, 1920. It was acknowledged that the event’s historical significance and the memories of the men had not been recognized with the gravity or permanence they deserved. For example, there was no mention of it in any of the textbooks used by ISD 709, Duluth’s own school district! Apparently a plaque had been in the sidewalk at the shrine building which noted the event but the plaque disappeared in the 1990’s when the sidewalks were repaired. Committees were formed to advance the mission of the CJM Memorial Board: • Education-to develop a curriculum for schools on the Lynching; • Public Awareness- a speaker’s bureau to talk in the community about the lynching; • Fundraising to create scholarships for youngsters to attend post high school education.

In a compelling and revealing example of the ongoing nature of white silence, the current Duluth police chief only found out in 2000 that it was his great aunt who had made the false rape accusation. (Duluth’s new police chief acknowledges great-aunt’s role in 1920 lynching) I will be in Duluth in October and will be visiting this memorial as a part of my own ongoing education.

On a final, more personal note, writing this post prompted me to wonder if there had been any lynchings in my area. Sadly, there was, in a community only about 30 miles from me. The historical newspaper account can be read here: Port Huron, Michigan Negro Lynching, and a more recent article here: Port Huron’s past included on lynching memorial. Time will tell if Port Huron will claim the memorial from the National Memorial for Peace and Justice.

Next week: Book break! I can’t totally walk away from the history of the marginalized, but this will be a new and different (and hopefully, fun) approach for me.

{{{DoReMI}}} – Not so much trepidation as anticipation of being nauseated and dealing with another round of nightmares. As I was/will anyway. I don’t like it. But my nausea and nightmares are nothing to the reality black folks faced. Are still facing to some extent. So as long as I can stay able to do my miniscule part in the Healing. Which includes listening to, hearing, the stories – and believing them.

Thank you for your on-going series, wherever it takes us, on the real history of racism in America. We have to know it before we can learn from it. We have to learn from it before we can do anything to Heal this vile, gangrenous, wound that is undermining all relationships. moar {{{HUGS}}}

You were far from the only one who expressed…anxiety, and it’s something I fully understand. When I bought Ifill’s book, I wasn’t sure I could even read it, but her emphasis on truth and reconciliation made it relatively nightmare-free. She talks a lot about white trauma and black trauma too. I stayed away from talking about black trauma, because it seemed presumptuous and “mighty white” of me; I didn’t even really talk about white trauma much, because without the context of black trauma, it would just sound like whitesplaining in the extreme. But even without her analysis, it’s easy to understand that sweeping this all under the rug helps no one heal. And goddess knows, healing is what we need if we are to move forward and create a new community.

Thank you. We must Heal this nasty wound. But we’ve got to get the toxic knife out of it first. All that’s going on right now is twisting it in the wound – has been since the 2016 election. But the plans to move forward are still out there even if the person who wrote those plans is not in a position to initiate implementing them. They were always going to take a “Village” to do that. We have to be the ones we’ve been waiting for. moar {{{HUGS}}}

Thank you, DoReMI, for a beautifully written essay about a gut-wrenching subject. I feel ashamed to be white. I think the government ought to make financial reparations to black people—not that such reparations would really compensate for the horrors endured by their ancestors and even themselves, but parting with money bespeaks a serious commitment.

I’m getting to where I loathe Christianity and all other patriarchal religions. I just can’t see anything good about religions that create an “other” (whether that other is black people, women, or infidels) and proceed to cruelly oppress that class.

If I live to be 100 I will never understand hatred of others.