Last week, I intended to write about two contrasting approaches to the extreme housing shortage that developed after the end of WWII, but as I started writing, it became obvious that the background about discriminatory housing practices needed to be explained and expanded first. With last week’s post in mind, this then is a snapshot of the development of Levittown, PA (never incorporated as a town, Levittown spans four different municipalities and three school districts). Next week, I’ll profile a second “city” which took a far different approach.

When Levitt and Sons was established in 1929, they didn’t know they would someday be known as the “Henry Ford of Housing.” Abraham Levitt was an attorney; his son William served as spokesman and president of the company, while his other son, Alfred was the company’s architect. They started out building a few hundred homes a year during the 1930s, and in the war years, they won a contract to build military housing in Norfolk, VA. In 1947, they entered the mass housing market in an even bigger way, with their first planned community in Levittown, NY (Long Island). Pent-up demand had created a housing shortage after the war, and Levitt and Sons built houses cheaply and quickly. They perfected a system where each house was built in 27 stages, with teams of workers specializing in one of the 27 steps rather than working on an entire house. This modified assembly line enabled each house to be completed in record time; in 1947, the teams were building 12 homes a day. The Long Island Levittown only offered two styles of home, another method of streamlining the production of the homes.

The actual building techniques used by Levitt, of course, are not those of which a carpenter’s guild would be likely to approve. He uses time and labor-saving machinery whenever possible, even when such use (as paint sprayers) is specifically forbidden by the union. Beginning with a trenching machine, through transit-mix trucks to haul concrete, to an automatic trowler that smoothes the foundation-slab, Levitt takes advantage of whatever economies mechanization can give him. The site of the houses becomes one vast assembly line, with trucks dropping off at each house the exact materials needed by the crew then moving up. Some parts–plumbing, staircases, window frames, cabinets–are actually prefabricated in the factory at Roslyn and brought to the house ready to install. The process might be called one of semi-prefabrication, in which a great deal of building is actually done on the site, but none that is unnecessary or that could be better done elsewhere–a lot of hammering, as Bill Levitt says, but very little sawing. Source: The Six Thousand Houses That Levitt Built, 1948, originally printed in Harper’s. 197:1180 (1948). 79-83.

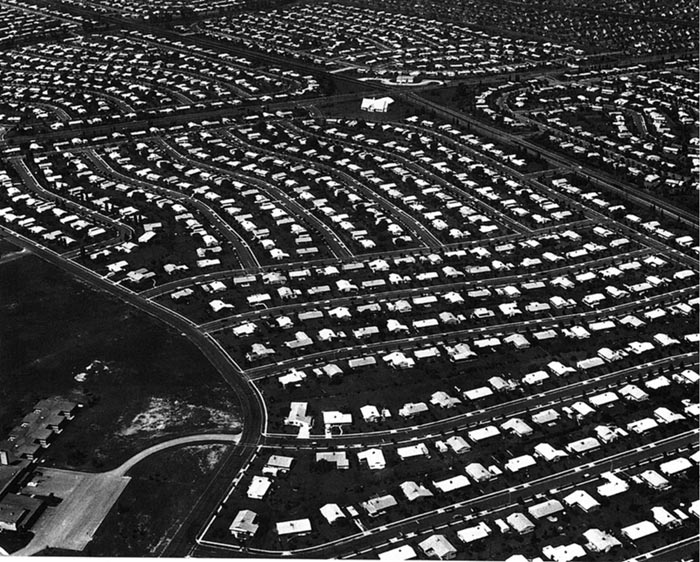

In 1951, Levitt and Sons was ready to build their next planned community. Learning from their experience in New York, they used surrogates to buy the land (from 150-175 separate landowners), so that they could own the area in its entirety without incurring the price war that their own purchase would have triggered. Within a few months, they owned 5750 acres in lower Bucks County, within proximity to the US Steel Fairless plant that was to be completed in 1952, highways, and the city centers of Philadelphia and Trenton. Similar to the New York community, Levittown, PA included master plans for baseball fields, swimming pools, shopping centers, and land for churches and schools. Houses were grouped into master blocks and sections, with each master block containing donated land for neighborhood schools. William Levitt’s goal was that,

no child will have to walk more than one half mile to school or cross any major road.”

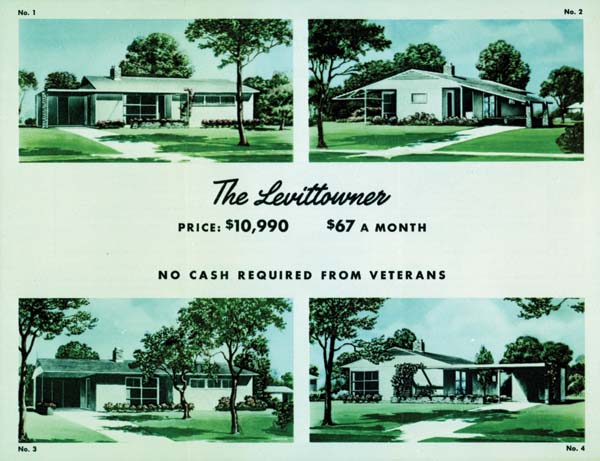

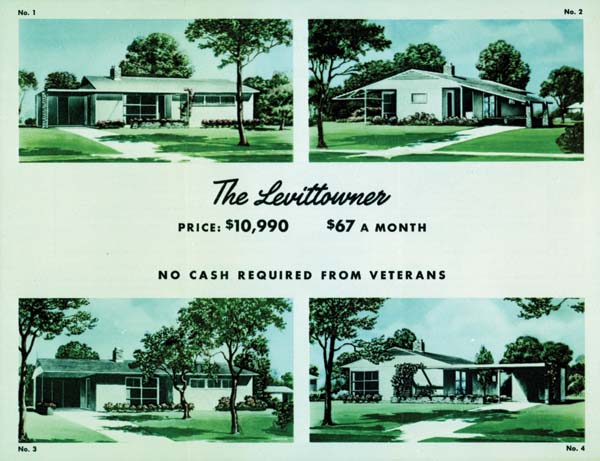

Having learned from criticisms of the NY project, Levittown, PA offered six different house models, but with the same financing and encouraging buyers to take full advantage of the GI Bill and VA loans.

Levitt was able to achieve his low prices and readily-available financing because he practiced “vertical integration.”

Bill Levitt is becoming a kind of bellwether of the building trades, and he believes that he is setting patterns which the others must eventually adopt. The housing industry, if it can properly be called an industry, has traditionally been based on limited construction by small contractors, consumer financing, and craft unions. Levitt & Sons are substituting mass construction by a single company, production financing, and either industrial unions or no unions at all…

…A house that goes up in Levittown will have been handled by Levitt & Sons from the start to finish. When Bill Levitt uses a favorite phrase, “vertical organization,” he is talking about a principle he has applied as rigorously as the housing business will allow. His lumber, for example comes from the Grizzly Park Lumber Company, of Blue Lake, California, which he owns. All of his appliances (a Bendix, say, or a GE refrigerator) are purchased from the North Shore Supply Company, which he owns. He doesn’t buy nails and concrete blocks; he makes them himself. Like most builders, he has many contractors working for him (the number varies in the neighborhood of fifty), but here also the vertical principle is retained. All of his contractors work for him and for no one else, and most of them were put in business by Levitt. Source: The Six Thousand Houses That Levitt Built, 1948, originally printed in Harper’s. 197:1180 (1948). 79-83.

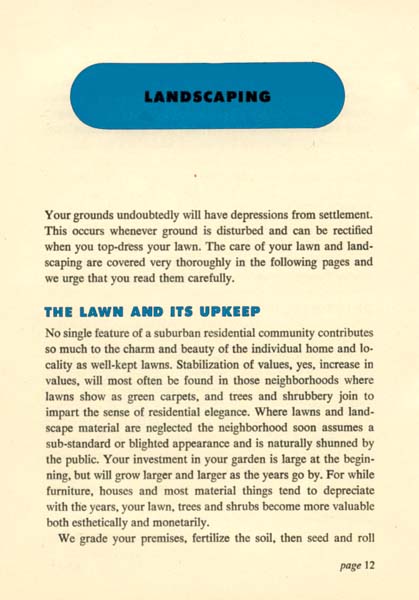

Affordable housing with easy financing came with some trade-offs for the buyer. William Levitt insisted that the community be standardized, and many of these requirements were written into the deeds. Fences were not allowed; if additional shrubs were planted (after the initial, standard landscaping provided by the company), they could not exceed 3′ in height. Lawn care was emphasized, and homeowners were issued instructions upon the purchase of a home. Additionally, the deed required that lawns be mowed weekly from 15 April-15 November. No more than two pets were allowed; no alterations to the exterior of the homes or carports were allowed – even painting had to done in the original color used by the company, unless the company gave permission for a change. Laundry could not be hung outside, except on temporary, mobile clothes lines provided by the company. Even then, laundry could not be hung to dry on Sundays or holidays, and the portable dryer had to be put away when not in use.

The one restriction missing from the deeds in Levittown, PA that had been present in the Levittown, NY deeds was the racial restriction. By the time building started for the Levittown, PA development, racial covenants had been ruled illegal and could not be included in deeds. William Levitt approached the change in the law in the way that made the most business sense to him: he ignored it. As one of the leading, most prolific builders in the country who had been on the cover of Time and featured in the Saturday Evening Post, it was a calculated move that held little risk. He was a builder who built communities based on conformity, so he felt secure that it was decision that would not cost him his customer base. He could and did systematically turn away African-Americans who applied to buy a house in Levittown. Additionally, he could disclaim responsibility for the redlining of real estate boards, since Levitt and Sons contracts were with the initial buyer, not those who became residents after a house was resold.

…African-American people were not allowed to buy homes in his developments. In a 1954 interview with the Saturday Evening Post, Levitt famously said that he and his company could try to solve a housing issue or solve a racial issue. It could not tackle both.

“If we sell one house to a Negro family, then 90 to 95 percent of our white customers will not buy into the community. That is their attitude, not ours. We did not create it, and we cannot cure it,” he said. Source: William Levitt: Father of Suburbia

William Levitt, however, had made one miscalculation. His Levittown, PA development was built in Quaker country, and the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) was headquartered in Philadelphia. The Friends were leading civil rights activists in the north, and the AFSC, in particular, had been looking for a way to start breaking down the psychological barriers of segregation. They viewed the creation of stable, racially-integrated communities as the key, and cracking open Levittown, a highly-visible symbol of closed housing, was viewed as a way to undermine discrimination. As early as 1953, AFSC activists were meeting secretly to plan strategy and figure out a way to open Levittown. They settled on a two-pronged approach: first, to find white families that would be willing to sell to African-Americans, and secondly, to find a black family that would be willing to be the pioneers in Levittown. Despite the housing shortage which hurt African-Americans to a greater degree than other Americans, finding the “right” family was not as easy as it sounded. The Friends were building on the ideas of a 1954 study of prejudice by Gordon Allport which found that

…interracial contact would not succeed unless the two groups that came into contact were of “equal status” and “seek common goals.” In this view, one that open housing activists embraced, any attempt to mix middle-class whites and poor blacks would fail miserably. Source: Sweet Land of Liberty: The Forgotten Struggle for Civil Rights in the North by Thomas Sugrue, p. 223

It wasn’t until 1957 that all the pieces fell into place. A white family had been trying to sell their home for the past two years while the country was in a recession. William and Daisy Myers, members of the Bucks County Human Relations Council, were in their mid-thirties. He was a WWII veteran and worked as a refrigerator technician; she was a schoolteacher. They had three children, a newborn, a three-year old, and a five-year old. In every way but skin color, they resembled the typical Levittown resident. But to many Levittowners, skin color was the only thing that mattered. When word leaked out that a black family had purchased a home, more than 2000 white Levittowners signed a petition opposing the Myers’ move:

As moral, religious, and law-abiding citizens, we feel that we are unprejudiced and undiscriminating in our wish to keep our community a closed community…to protect our own. Source: Sweet Land of Liberty: The Forgotten Struggle for Civil Rights in the North by Thomas Sugrue, p. 224

The claim of law-abiding didn’t last past the first day of the Myers’ arrival. Nine days of protests, rock throwing, cross burning, and angry mobs in front of the Myers’ house occur; it isn’t until a police officer is severely injured and the state police announce their intention to allow no more protests that the most visible protests fade away. (A good timeline of the events is here: 60 years later, the Levittown shame that still lingers)

The Myers family were pioneers; in 1958, another black family moved into Levittown without the rash of violence that greeted the Myers. The Myers family lived in Levittown for four years before moving to York, PA. But it’s difficult to deem their actions a success; in the 2010 census, the population of Levittown was 90.41% white.

Even today, Conn noted, the two Levittown communities are majority white. “If you look at the demographics of suburbia over the second half of the 20th century, it really is racially red-lined and that’s part of the model that the Levitt brothers put in place,” he said. William Levitt: Father of Suburbia

Next week: A Tale of Two “Cities”: Concord Park

Good morning everybody. Thanks for the continuing storyline, DoReMi. Although I applaud their “mass production” techniques at a time when housing was in big demand, their “I’m not racist but my buyers are” persona was a big pile of 💩. No matter how you look at it.

Showers this morning to start May Day off right (no basket on my porch, though). Coffee.

Levitt seems to be equally admired and reviled in the community planning/architecture circles. The next time I talk to either of my cousins who are architects, I’ll be sure to ask how they feel about his influence. He did do some innovative things with his homes. Although the homes were built on slabs, the slabs were built with radiant heat systems. His kitchens were designed with built-in appliances, which was a fairly novel approach for the time. The attics were designed with the possibility of being converted to rumpus rooms or an additional bedroom in mind (at the owner’s expense, of course). A lot of his mass-production ideas are still used today…any time you see a house going up with pre-made trusses, Levitt can be credited.

On the other hand, suburban sprawl is also his legacy. Although he planned master blocks and sections to create the feeling of small town neighborhoods, he also created bedroom communities with no larger tax base. Most planners today understand that mixed-use communities are necessary so that homeowners don’t bear the tax load alone.

{{{DoReMI}}} – My mother was of the opinion that we may never solve systemic racism (not that she called it that) but we cannot solve it unless/until we integrate neighborhoods. That folks have to live close enough to each other to see that people are people and get comfortable with each other. Considering what neighborhoods are these days – most kids don’t walk to school even if it’s 2 blocks, never mind half a mile – and that most folks don’t know their neighbors I don’t know if even that will work. But I still think she’s right. Integrated (which isn’t the same as desegregated) housing is the foundation. There’s a very great difference between going to integrated school/work then home to segregated neighborhoods & going to segregated school/work then home to integrated neighborhoods. The few years I lived in what I thought was becoming one were wonderful. moar {{{HUGS}}}

Your mother was right, of course, but the ongoing struggle is stupid white people who choose flight over familiarity. Even the argument about declining property values when “They” move in is more myth than fact, although it can become a self-fulfilling prophecy if white flight commences. Studies have shown that stability is a great contributor to the value of a neighborhood. That explains why today the houses in the PA Levittown have an average market value above $200K, while the homes in the NJ Levittown (now Willingboro, NJ) are lower at about $160K, even though those houses are more varied with higher-end models. Willingboro desegregated comparatively rapidly, and by the 1970s, a white exodus was in full flight. It’s highly likely that the resulting instability in the market has contributed to the lesser home values, even today.

I understand about white flight of stupid white people – or at least racist white people. My mother had 3 younger sisters, all 3 white-flighted out of Houston in the late ’60s. For that matter at least one of my own younger siblings is racist enough to have white-flighted out of Houston. The other 3 all headed for rural rather than suburban areas so I don’t know if it was deliberate or accident that the areas are predominantly white. And of course racism comes in many shades – one of those sisters is married to a Latino whose family was in Texas before it was Texas but still gets pulled over by cops because he (a retired engineer 30 years with the state) shouldn’t be driving such a nice car unless he’s a drug dealer – so she’s obviously not racist as far as Latinos are concerned. Not sure about as far as blacks are concerned. sigh.

In Little Rock in the mid-1950s we lived next door to a black couple—empty nesters—and thought nothing of it. They were our neighbors! As a young girl I loved to bake, so when I made a cake I’d always take a couple of slices to Mr. and Mrs. Johnson and ask them to try it. My mother and Mrs. Johnson used to chat while they were hanging out their clothes in the backyard. The Johnsons had owned property on that block for 30 years.

To us, this was perfectly normal.

That’s the way it should have been, should be. Even in my teens Momma had to explain why having the black family move in next door was such an important (and wonderful) event. I didn’t think anything of it. New neighbors are always new – you greet them, help them move in, and see what sort of relationships develop. When you’re dealing with a married couple plus a divorcee for the adults and 5 kids per family ranging from the eldest of me (I think I was 12 when they moved in, might have been 13) to the baby she had right after they moved in, well, that’s a lot of relationships to develop. :) Most were friendly, none were unfriendly – just neighbors.

DoReMI, thanks for this interesting and well-written post! I find these bits of history fascinating. I’ll look forward to your next in the series.